Slope stability is a fundamental concern in open-pit mining, influencing not only the physical integrity of the mine but also the safety, productivity, and financial viability of the entire operation. It refers to the ability of pit walls, benches, and overall slope configurations to maintain structural integrity over time under various geological and operational stresses. Maintaining stable slopes is not merely a technical requirement but a critical factor that directly impacts operational continuity and risk management.

Slope stability is a fundamental concern in open-pit mining, influencing not only the physical integrity of the mine but also the safety, productivity, and financial viability of the entire operation. It refers to the ability of pit walls, benches, and overall slope configurations to maintain structural integrity over time under various geological and operational stresses. Maintaining stable slopes is not merely a technical requirement but a critical factor that directly impacts operational continuity and risk management.

The importance of slope stability cannot be overstated. Open-pit mines are inherently dynamic environments where continuous excavation alters the stress distribution within the surrounding rock mass. Poorly designed slopes can lead to catastrophic failures – events that have, in some cases, halted operations for months, damaged expensive equipment, and tragically resulted in injuries or fatalities. These failures also carry extensive financial consequences, from remediation costs to legal liabilities and reputational damage.

The Balancing Act: Safety vs. Profitability

Slope stability is not a one-time calculation; it is an ongoing engineering challenge that evolves throughout the life of the mine. As the pit deepens, the stress fields change, groundwater conditions evolve, and previously minor geological features can become significant risks. Each stage of pit development requires a reassessment of slope designs to ensure they remain within acceptable safety margins. This continuous evaluation is essential for minimizing operational risks while optimizing the overall mine design for economic efficiency.

A key challenge in open-pit mining is finding the balance between maximizing pit dimensions – thereby reducing strip ratios and improving economic returns – and maintaining slope angles that are stable over the long term. Steeper slopes allow for less waste removal and more efficient access to ore, but they inherently increase the risk of failure. Conversely, overly conservative slopes may reduce risk but at the cost of leaving significant amounts of valuable material unmined. This trade-off is at the heart of slope design and requires sophisticated analysis and decision-making.

Complexity of Slope Stability Analysis

Adding to the complexity are the wide-ranging factors that influence slope stability. Geological structures, including faults, joints, bedding planes, and shear zones, play a critical role. Hydrogeological conditions, such as the presence of groundwater and pore water pressures, can drastically reduce slope strength. External dynamic factors like seismic activity, blasting-induced vibrations, and even extreme weather events further complicate the analysis. Each of these variables must be carefully evaluated to produce reliable slope designs.

Traditional approaches to slope stability relied heavily on empirical methods and engineering judgment. While these methods remain valuable for preliminary assessments, modern mining operations require more precise and robust analytical tools. This need has driven the development and adoption of advanced computational techniques that can accurately simulate complex geological conditions and predict slope behavior under various scenarios.

Comprehensive Capabilities with K-MINE Tools

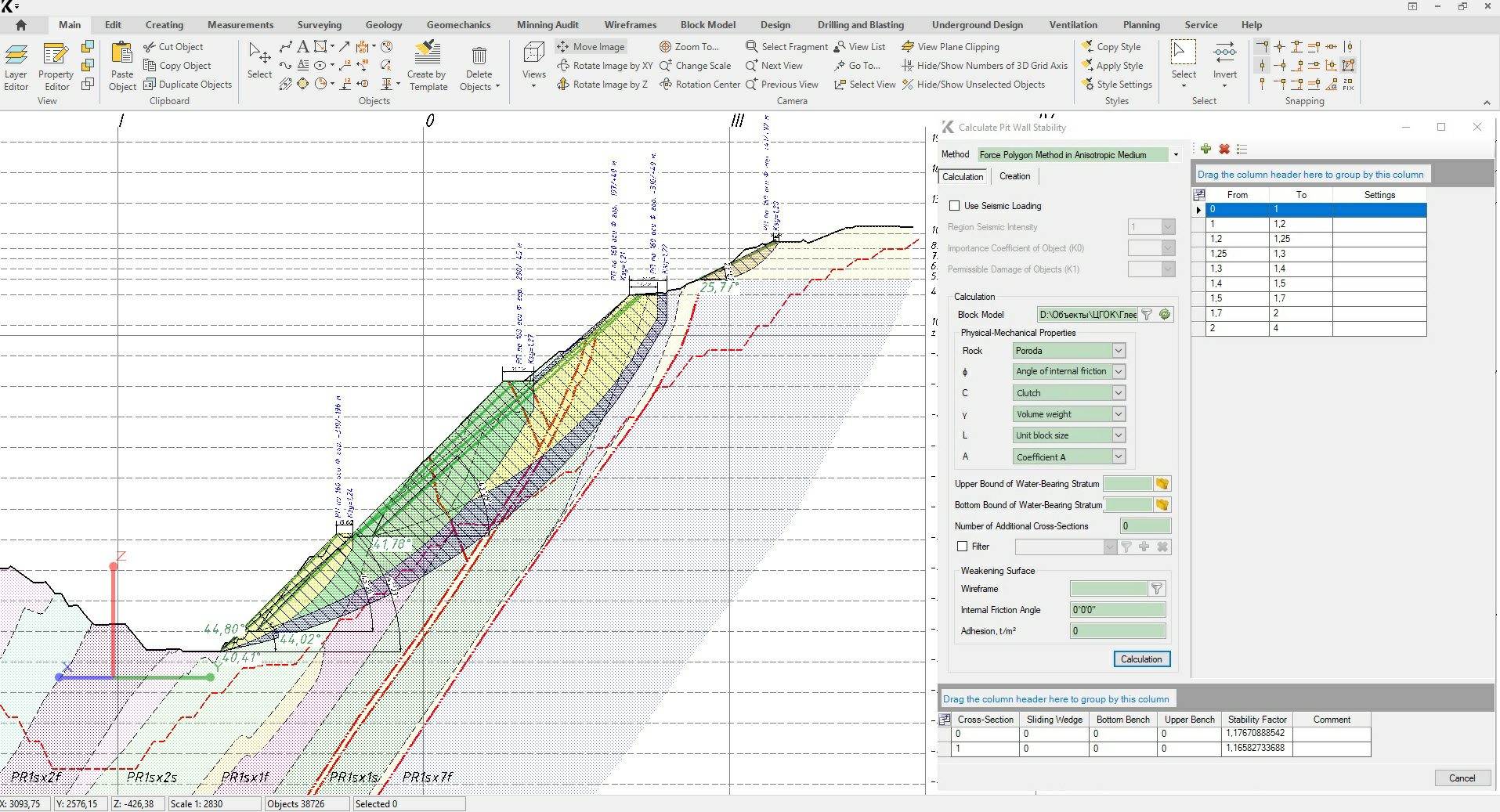

K-MINE’s slope stability tools are designed to handle both routine and highly complex problems. The software provides an intuitive interface for setting up models, defining material properties, and specifying boundary conditions. Users can easily create cross-sections for analysis, assign geotechnical parameters, and select the appropriate analysis method. Visualization tools allow for real-time interpretation of results, including FoS distributions, deformation patterns, and stress fields.

One of the key advantages of K-MINE’s approach is the seamless integration of geological, geotechnical, and hydrogeological data. Engineers can import data directly from block models, drill holes, and geological interpretations. This integration ensures that stability analyses are based on the most accurate and up-to-date information available. Additionally, the ability to run multiple scenarios quickly enables engineers to test various design options, assess risk levels, and optimize slope geometries for both safety and economic performance.

What’s Next: A Step-by-Step Approach

In this article, we will delve into the practical application of slope stability analysis using K-MINE. We will examine how different methods – empirical assessments, Limit Equilibrium, and Finite Element Modeling – can be applied effectively based on project complexity. Through this step-by-step guide, mining professionals will gain a clear understanding of how to navigate slope stability challenges using K-MINE’s powerful analytical tools.

Approaches to Slope Stability Assessment

Empirical Methods – Fast, Practical, but Limited

Empirical approaches are the most straightforward way to assess slope stability and have been widely used since the mid-20th century. These methods emerged from the need to simplify complex geotechnical evaluations based on direct observations in the field. Systems like the Rock Mass Rating (RMR), Q-System, and Geological Strength Index (GSI) were developed by rock mechanics researchers such as Bieniawski and Barton, who transformed field data into practical classification systems.

These methods are most appropriate at the early stages of mine design or when quick decisions are needed. They are invaluable when detailed site investigations are incomplete but some preliminary understanding of the rock mass exists. If the project is in the conceptual stage, or if a slope requires a rapid check to determine whether more detailed analysis is necessary, empirical methods provide a fast and simple solution.

The principle is straightforward: by assessing rock quality based on features like joint spacing, weathering, groundwater presence, and strength properties, engineers can assign numerical ratings that correspond to recommended slope angles. A higher rating typically allows steeper slopes, while a lower rating indicates the need for flatter, safer geometries.

In K-MINE, empirical analysis integrates directly with geological models. Users can assign rock mass quality indicators within block models or cross-sections, enabling immediate visual feedback on where slopes are likely to be more or less stable. However, the simplicity of this approach comes with limitations – it does not account for detailed geometries, groundwater flow, or structural features like faults or shear zones. As a result, empirical methods are best viewed as a first step in a comprehensive slope stability workflow, not a final answer.

Limit Equilibrium Method (LEM) – The Engineering Standard

The Limit Equilibrium Method has been the backbone of slope stability analysis for over seventy years. Originally developed through the work of Karl Fellenius in the 1930s and later refined by researchers like Bishop, Janbu, Morgenstern, and Price, LEM formalized the balance of forces acting on potential failure surfaces into a mathematically rigorous framework.

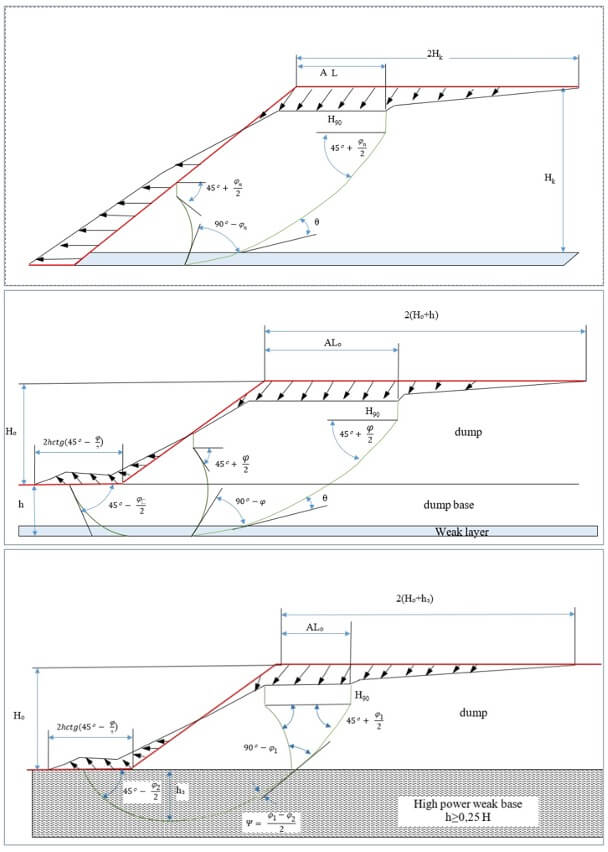

LEM is widely regarded as the standard approach for analyzing slope stability in open-pit mines. It is most effective when dealing with relatively simple to moderately complex conditions: homogeneous rock masses, stratified but predictable geology, and failure mechanisms dominated by sliding rather than progressive deformation.

The strength of this method lies in its clear mechanical interpretation. It assumes a potential slip surface – either circular or non-circular – and evaluates whether the resisting forces (cohesion, friction, and inter-slice forces) are sufficient to counteract driving forces like gravity, water pressure, and external loads. The result is the Factor of Safety (FoS), a simple yet powerful indicator of stability.

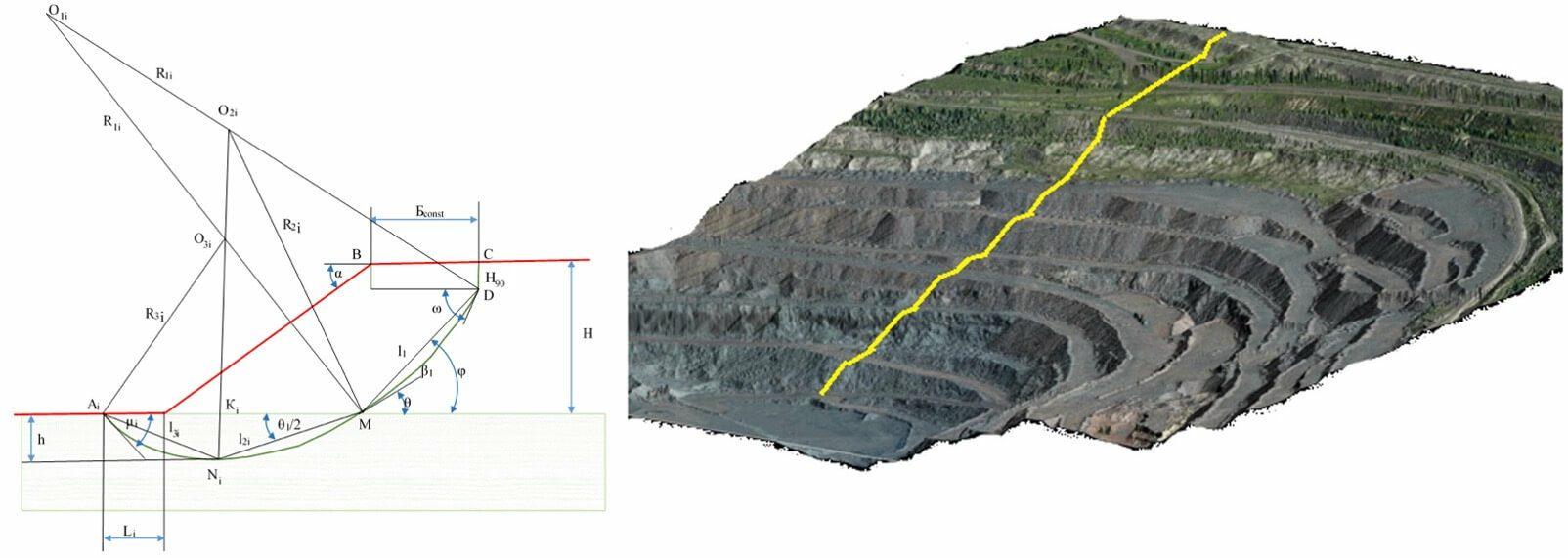

In K-MINE, setting up a LEM analysis is intuitive. Engineers begin by constructing cross-sections through critical parts of the pit. Rock mass properties, groundwater conditions, and any relevant external forces are then assigned. The software automatically searches for the most critical slip surface, calculating FoS and visualizing both the geometry of the potential failure and the distribution of safety factors across the slope.

What makes LEM so widely adopted is the balance between computational efficiency and engineering accuracy for typical mining scenarios. However, LEM does carry assumptions: it treats the rock mass as rigid-plastic, ignores internal stress redistribution after partial failure, and cannot easily model progressive or ductile failures. In slopes influenced by complex structures, deep-seated weakness zones, or anisotropic materials, the limitations of LEM become more pronounced, signaling the need for more advanced modeling techniques.

Finite Element Method (FEM) – Advanced Modeling for Complex Problems

The Finite Element Method (FEM) is one of the most powerful and versatile tools in geotechnical engineering. Originally developed in the 1950s for structural analysis, FEM quickly became indispensable in rock mechanics and slope stability studies, offering capabilities far beyond traditional methods like Limit Equilibrium.

The core strength of FEM lies in its ability to simulate how stresses, strains, and displacements develop throughout an entire rock mass without assuming any predefined failure surface. Instead of focusing on a potential slip plane, FEM models the stress-strain behavior of materials under various loads and boundary conditions, allowing failure mechanisms to emerge naturally from the analysis.

This approach becomes essential when dealing with slopes characterized by complex geology, anisotropy, multiple intersecting faults, or significant groundwater effects. It is particularly useful in evaluating deep pit walls, high slopes, and final wall designs where the consequences of failure are critical.

In K-MINE, the user first creates a geological section with polygons and defines boundary conditions with polylines. Then, rock properties such as elastic parameters, strength criteria (Mohr-Coulomb or Hoek-Brown), and mesh size are assigned for each geological unit. Boundary conditions restricting movement along specified axes are set, after which the finite element mesh is generated. Once the setup is complete, the system calculates the stress-strain state and the safety factor using the strength reduction method, producing detailed contour plots and displacement fields as results.

The results provide comprehensive insight into the slope’s behavior, including the distribution of stresses, areas of plastic deformation, displacement vectors, and progressive failure development. This enables mining engineers to understand not just whether a slope is stable, but how it behaves under evolving operational conditions.

FEM analysis in K-MINE is the tool of choice when precise assessment of deformation, stress redistribution, and failure progression is necessary. It offers unmatched flexibility and depth for slopes where simplified models are inadequate.

Stability of Heterogeneous Walls – FEM Tailored for Complex Geological Structures

While the general FEM analysis in K-MINE is designed for versatile geotechnical modeling, the task “Calculate Stability of Heterogeneous Walls” is a specialized implementation of the FEM approach, specifically optimized for evaluating slopes composed of geologically diverse materials.

This tool was developed to address scenarios where traditional slope stability analysis becomes inefficient due to the presence of highly heterogeneous geological conditions – including layered rock masses, variable lithologies, zones of weakness, and complex structural features.

Unlike the classic FEM task, which is highly flexible and general-purpose, “Calculate Stability of Heterogeneous Walls” streamlines the modeling process specifically for slope stability problems with geological complexity. It allows engineers to rapidly define slopes with multiple geological units, assign varying mechanical properties, and simulate how each layer or structural domain behaves under operational loads.

The workflow involves selecting the slope geometry, defining material models for each lithological unit, setting groundwater conditions, and applying boundary constraints. The system then automatically generates a finite element mesh tailored to the heterogeneous structure and runs the stability analysis.

The outputs are similar to general FEM – including stress distribution, displacement fields, and identification of plastic failure zones – but the process is optimized for handling geologically layered or segmented walls more efficiently.

“Calculate Stability of Heterogeneous Walls” is particularly valuable when analyzing pit walls where stratigraphy plays a dominant role in controlling failure mechanisms. It excels in situations where the interaction between strong and weak layers leads to complex deformation patterns that simple models cannot capture.

By providing a more guided and efficient workflow for heterogeneous slopes, this tool complements the general FEM analysis. It allows mining engineers to focus specifically on the challenges posed by layered geology without compromising the depth and accuracy of the simulation.

Closing Thoughts on Method Selection

Each method – empirical, LEM, and FEM – serves a distinct role in slope stability analysis. Empirical methods offer speed and simplicity for early decisions; LEM provides reliable, practical results for typical slope configurations; FEM delivers the deep insights needed for the most complex and high-risk scenarios. What’s crucial is knowing when to apply each method. K-MINE’s integrated toolkit empowers engineers to navigate this decision-making process efficiently, ensuring that slope designs are not only safe but also economically optimized.

Back

Back