Every professional manager in the mining industry knows that maximizing profit depends on how optimally mining operations are executed. In other words: what should be extracted at a given time, in what quantity, with what quality, and where the material should be directed. All over the world, thousands of engineers work on this question at any given moment – aiming to minimize waste stripping while maximizing the recovery of valuable material and considering all mining and technical factors with regard to the company’s future.

Every professional manager in the mining industry knows that maximizing profit depends on how optimally mining operations are executed. In other words: what should be extracted at a given time, in what quantity, with what quality, and where the material should be directed. All over the world, thousands of engineers work on this question at any given moment – aiming to minimize waste stripping while maximizing the recovery of valuable material and considering all mining and technical factors with regard to the company’s future.

After all, no one wants to run out of ore ready for extraction. In this article, we will visually demonstrate how the issue of production optimization can be solved using the K-MINE software.

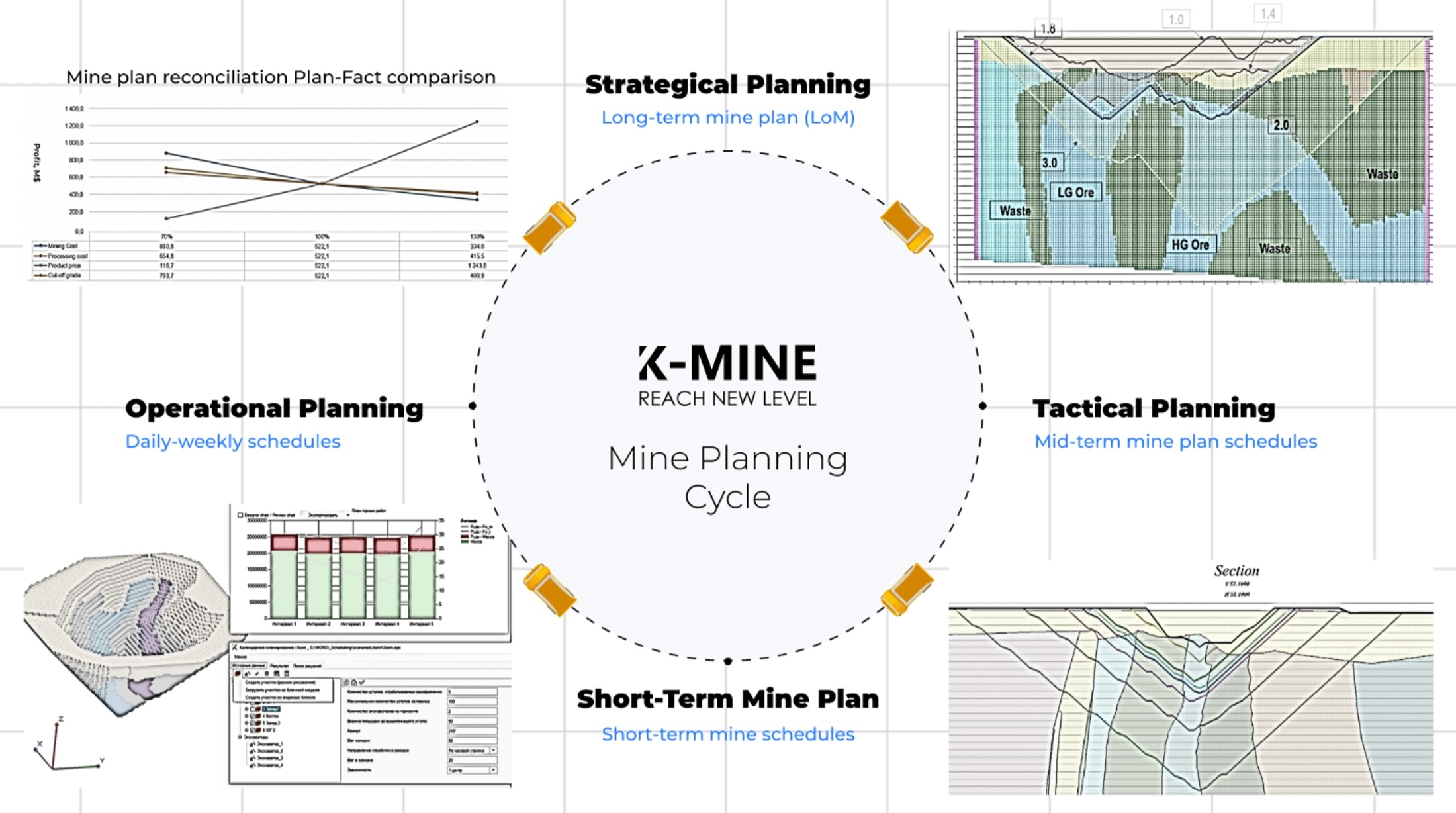

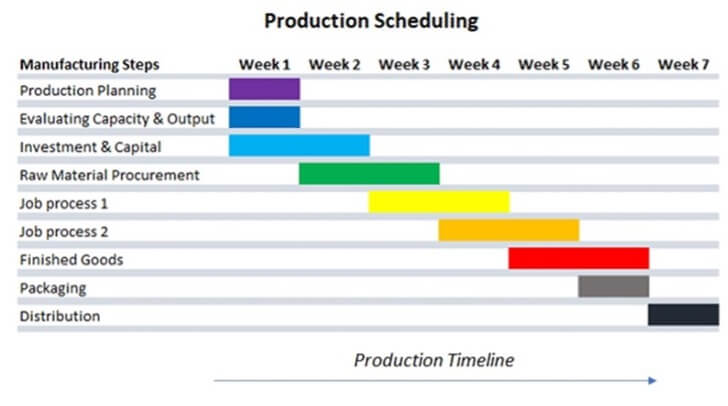

To begin, it is worth recalling the basic principles of mine planning and the core processes involved. The most important rule in planning is adhering to the company’s conceptual principles and maintaining production at the required quantity and quality. It may sound simple, but ensuring this principle requires following certain steps and processes during planning. The planning concept is based on continuity – one interval transitions into the next, and it is essential to follow the results of previous planning stages to achieve the company’s strategic objectives. Let’s look at a clear example of what the planning cycle looks like.

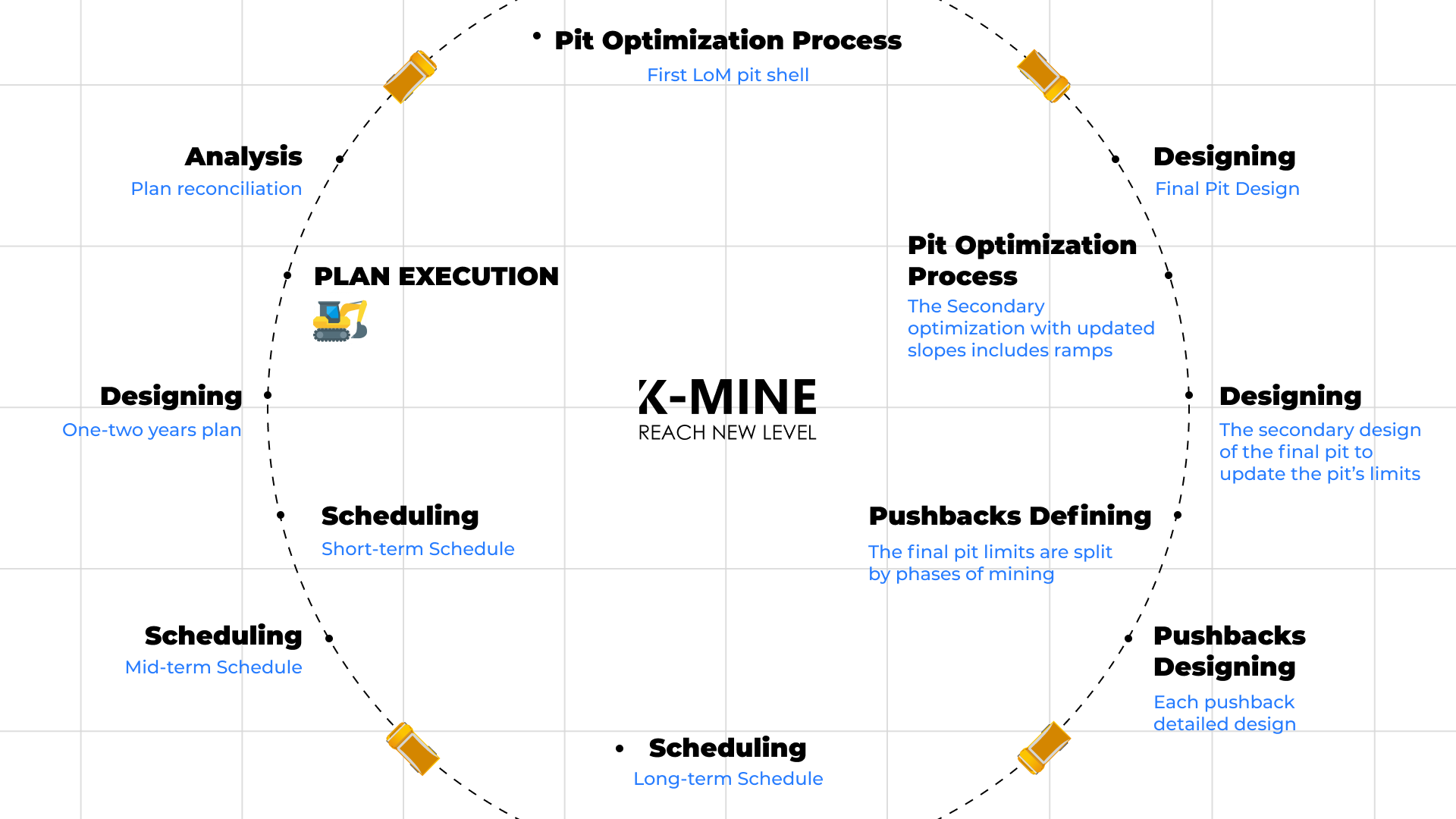

If we talk about the starting point, everything begins with deposit optimization. We have already written an article on this topic, and here is the link for those who want a deeper dive into strategic planning: Mastering Open Pit Optimization

Next, we use the results of the optimization to create pushback designs. With these pushbacks, we begin building long-term mine production plans. The outputs – most often wireframes – are then used in medium-term planning. Our pushbacks can be modified or downsized to provide greater flexibility; in this form, they are referred to as cutbacks and are constrained by the results of the previous planning period. Based on them, medium-term mining plans are created. After that, a similar approach is applied, but with higher detail, for short-term planning. The areas become even smaller, with significantly more attention to the details of their extraction, equipment, timing, interactions, and so on.

Let’s take a look at all these planning processes through a visual example to see how this may appear from a best-practice perspective.

An essential and inseparable stage of planning is Analysis. Improving the plan cannot be achieved without constantly evaluating performance results and comparing them to the plan. The reasons for deviations must be identified, considered, and incorporated into the next iterations of plan development. From an analytical standpoint, several approaches add transparency and leave only the need to make specific decisions aimed at reducing the gap between planned and actual performance.

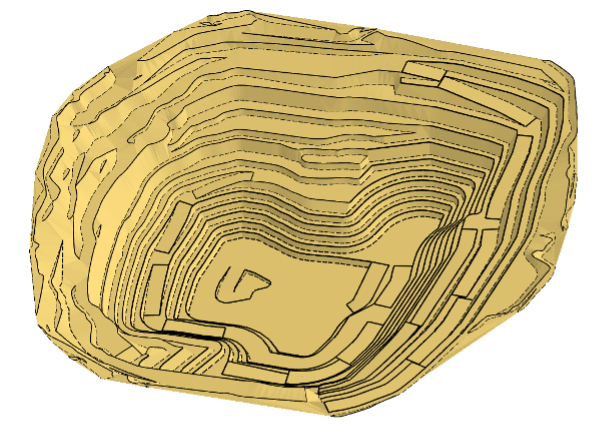

Long-Term Planning Strategies and Automated Search

We will cover this in detail in future articles, but for now, let’s focus on our main topic – calendar (schedule-based) planning. As we can see, the first stage is long-term planning. For this, the most commonly used inputs are the designed pushbacks, which represent completed stages of the pit. The core idea of long-term planning is to determine which pushback, and in what volume, must be mined in order to follow the company’s objectives. Here is what designed pushbacks may look like: they must clearly reflect the haulage network and the potential for pit expansion for subsequent pushbacks. Additionally, each pushback must be a continuation of the previous one – or several at once. This creates certain complexities, but everything can be resolved with dynamic design in K-MINE and the appropriate skillset.

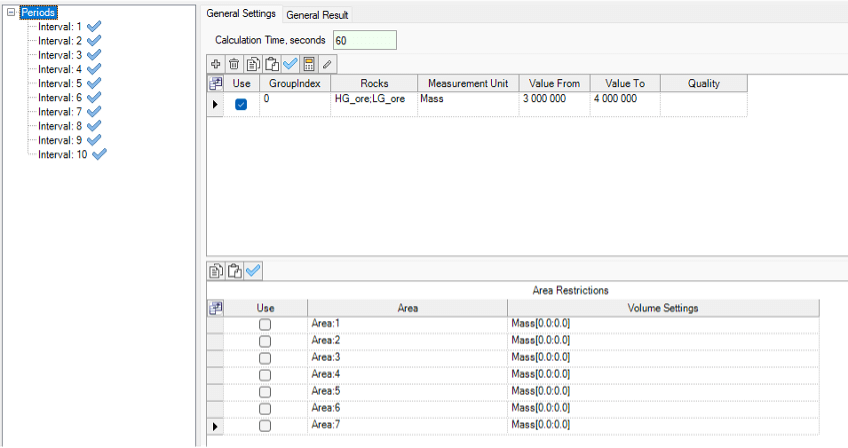

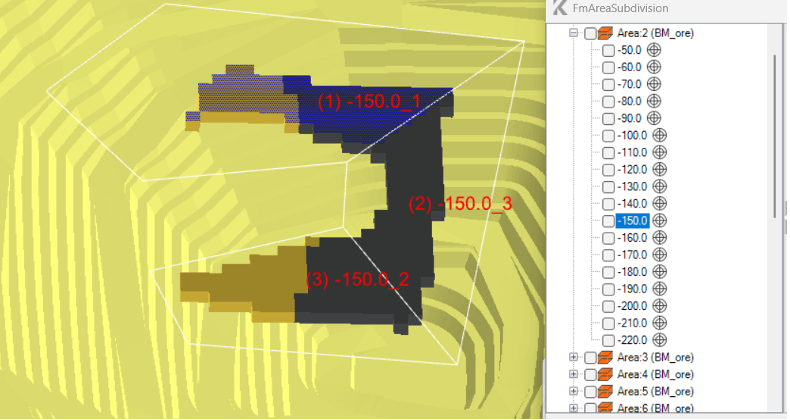

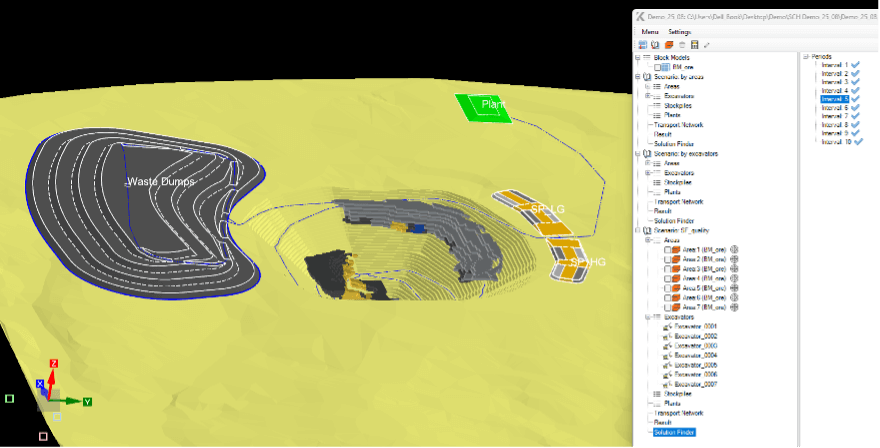

With the pushbacks in place, we can move on to the actual planning stage. First, we load the block model and define the areas by constraining it. After that, we configure each area – mining direction, dependencies, and other parameters. The setup is straightforward and intuitive. Once the areas are ready, we create the planning intervals and switch to the automatic search mode. For long-term planning, this is the most effective and relevant tool.

A few words about how the automatic search works. It evaluates all feasible combinations to identify solutions that meet the specified targets. Which means:

- The more areas we define, the more combinations the system has to explore

- The more input constraints we set – especially strict ones – the fewer combinations remain available

Understanding this helps us request outcomes that are actually achievable. Everyone would love to extract only valuable ore and forget about waste stripping – and some of you have probably heard similar suggestions from the economics team, since waste doesn’t generate revenue. Sounds nice, but reality works differently.

If we are unsure what the realistic targets should be, we can still start with broader settings and gradually refine them until we reach a viable solution. Let’s look at the functionality in more detail – what it can do – and then try it in practice.

- Set target parameters that apply either to all intervals or individually to each one.

- Copy search settings from one interval to another.

- Create unique conditions for finding solutions, apply constraints, and enforce specific requirements.

- Calculate a single interval or a group of intervals at the same time.

- Direct the solution search according to the criteria we define.

Now let’s look at what these capabilities actually give us. As one option, the first calculation can be run with the search focused only on the valuable material, without applying any additional constraints, just to see where the algorithm identifies ore. But this result will not be final – it will need refinement. The point is that since we did not limit waste stripping, some periods will show excessive waste, while others will show too little.

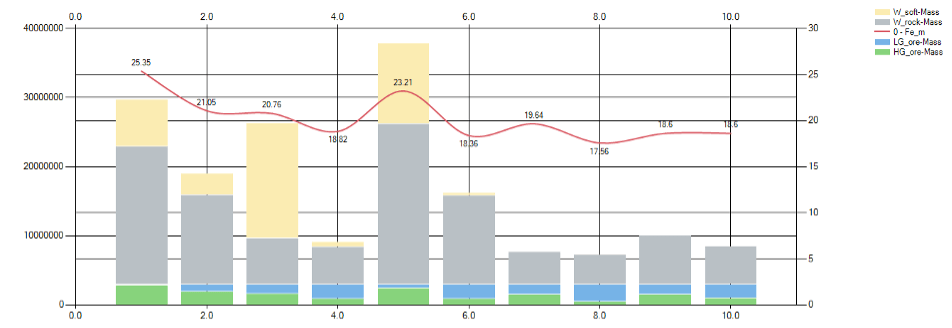

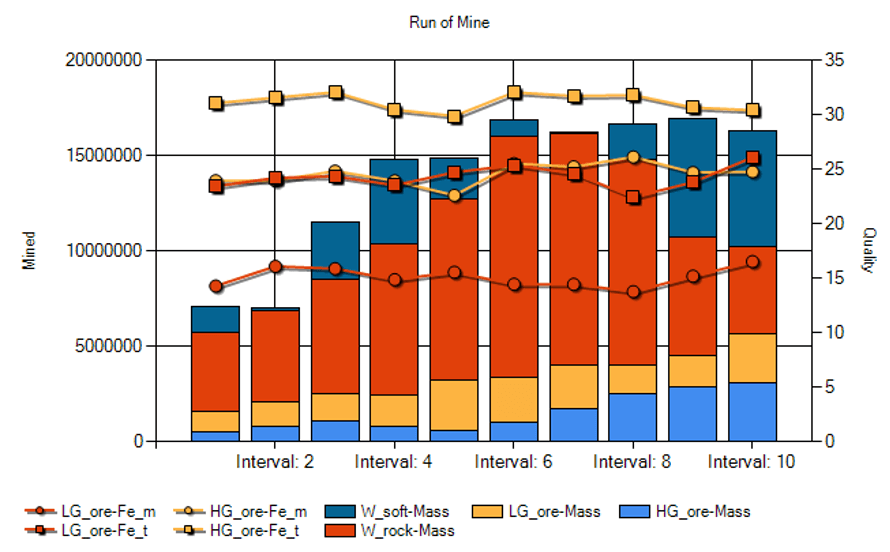

For example, here is the kind of output we may get. The data is shown in chart mode, which makes it easier to interpret. In K-MINE, you can always generate a chart whenever a table is available. This applies to any data, which is useful both for geology and for planning.

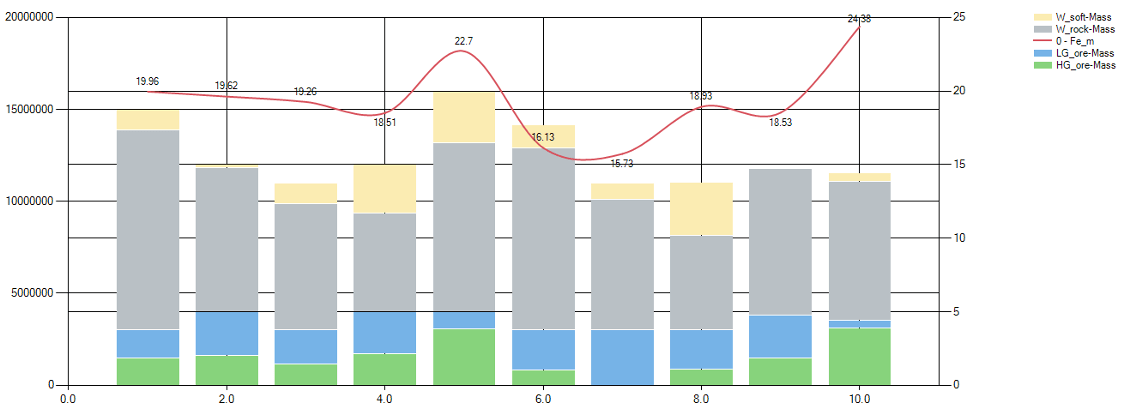

From this chart, we can clearly see how much waste must be mined to meet specific ore production targets. The next step may be to try smoothing the waste stripping rate. To do this, we simply add the required values to the search targets. The outcome may look like this:

As we can see, the waste stripping rate has indeed been smoothed, which is a positive sign. To achieve an even more uniform result, stricter constraints can be applied – but it is important to remember that the target must remain realistic. Minor fluctuations are acceptable in medium-term planning, as they will be balanced out in subsequent cycles.

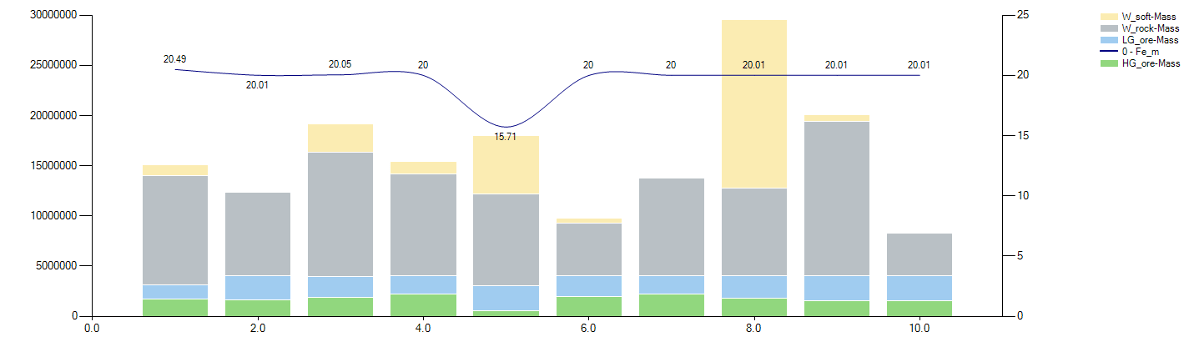

Each plan must also be supported by confidence in the quality parameters. Quality can be added as an additional target, and in that case, the chart will take the following form:

Quality has been brought under control, except for one interval where it was impossible to meet the target. The chart also shows that the waste quantity changed as well. All of this is a normal part of searching for an optimal material haulage plan. This approach helps us track how the plan behaves and how it reacts to different input parameters. With this understanding – and with a sense of “what happens if…” – we continue refining the plan until we reach the optimal result.

Now a few recommendations for situations where the targets still cannot be met. The most common reason is a lack of available combinations for the solver. Lowering the requirements is usually not an option, because management always expects an excellent plan. So our only choice is to increase variability.

This means:

- Review the pushbacks. If a pushback contains zones with excessive width, split it into cutbacks and reduce its volume. This makes it possible to reach the ore faster since the waste requirement becomes smaller.

- Review the mining parameters of the pushback. In some cases, adding equipment to accelerate waste stripping may help. Once the ore is exposed, the intensity can return to the desired level.

- The simplest solution for any engineer is to target the ore that is closest to the surface and force the system to mine there. But this leads to a situation where waste requirements must increase exponentially in later periods. What to do? For example, suppose Pushback 1 is already exposed and producing ore, Pushback 2 is being stripped, and Pushback 3 is next. If we see that waste will spike significantly in Period 5 to meet the targets, we can start gradually increasing waste from Period 1 onward. This allows us to reach Period 5 without drastic jumps. It is essential to see the full picture – not only the first few years but the entire life of the deposit – to ensure stable ore delivery to the plant.

- In practice, I have often needed to deliberately slow the development of high-grade ore zones to preserve flexibility for future blending. In other words, it is important to track the average grade across the deposit and avoid exceeding it too early. By applying these simple principles, any engineer can achieve the required targets.

Transitioning to Medium-Term Feasibility

Once the targets are met, we move to the next planning stage – medium-term planning. What is required for a proper transition? We need the results of the long-term plan, which in our case are the wireframes. We export the wireframes and “slice” them into new areas.

Our scheduling module also allows a quick transition between planning stages. You simply open the context menu of the desired interval in the solution search and choose “Create scenario based on results.” This generates a new scenario containing only those pushbacks that were used in the selected interval, and only in the volume that was actually mined. From there, you can continue building a more detailed plan.

This covers the long-term planning capabilities. In most cases, medium-term planning differs from long-term planning only by the addition of equipment-related constraints. In other words, if your long-term plan is structured by individual years rather than five-year blocks, the next step is to verify whether it can be executed with the available fleet.

How to do this? The simplest approach is to calculate the productivity of each unit of equipment and determine where it should operate. Medium-term planning requires higher detail, which often means adjusting the size of the areas so they are easier to manage – now we must also consider where the equipment will physically be placed. If an area must progress quickly according to the long-term plan, it may require more than one machine, so the width must allow it. This can be done in Excel or through our plugin. The scheduling module already allows placing excavators on areas, monitoring their work, and moving them if needed.

If an area progresses slowly, there is no point in keeping equipment there for the entire interval. You may assign a low-productivity unit or temporarily relocate a machine from a neighboring area. These are exactly the types of questions addressed at the medium-term stage. A long-term plan must be executable.

If the long-term targets cannot be met within the medium-term constraints, this is not a problem. We can simply adjust the long-term plan based on the insights gained from the medium-term plan. Experienced mining engineers already think ahead about medium-term feasibility while working on the long-term design. This can simplify the medium-term stage or even eliminate it. This happens when a long-term plan is created with high detail – using actual equipment and annual intervals rather than five-year cycles. Five-year blocks can still be used in later stages, but without disrupting the medium-term process.

Medium-term planning confirms that the long-term plan can be executed with the available fleet and technology. In other words, this stage introduces tactical elements – how exactly the company will achieve its long-term goals over the next 5 to 10 years. Excessive detail is not required; it is enough to confirm conceptual feasibility.

The material haulage charts should remain relatively smooth, without significant spikes, and maintain both ore quantity and quality. Overall, they must align with the long-term plan. Regarding equipment, only major repairs that affect production – typically two weeks or more (this threshold may vary based on engineer experience) – are considered. The outputs of this stage include tables, charts, wireframes, and polylines when necessary.

With this, we move to the final planning stage – short-term planning.

At this stage of planning, detail is essential. Here, we must account for as many operational conditions as possible and link the main processes together.

At this stage of planning, detail is essential. Here, we must account for as many operational conditions as possible and link the main processes together.

These processes may include, for example:

- Surveying the block before drilling

- Cleaning and preparing the block

- Re-surveying and transferring the data for design + block design • Charging

- Blasting

- Start of excavation

All these processes are familiar to mining engineers, and the planner’s task is to connect them in a coordinated workflow to ensure systematic extraction in the short-term period. A typical short-term period is one month – the timeframe that must be planned with the highest level of detail. In general, short-term planning may cover anywhere from three months to two years, depending on various factors such as deposit size. Therefore, we must understand equipment allocation at every moment of plan execution, plus at least one month ahead.

This is the most challenging planning stage. It requires the most time due to the number of influencing factors, unexpected events, and the dynamic nature of mining operations.

Let’s look at what needs to be adjusted and configured in the scheduling project to transition into short-term planning mode:

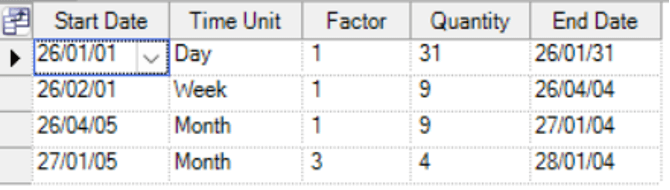

1. Planning periods. Adjust them according to the requirements. In most cases, a combined structure is used: one month broken down by days, the next two months by weeks, and the remaining months of the year by months. This way, each period transitions smoothly into the next. An additional yearly layer divided into quarters can also be added.

2. Adjusting the planning areas. This involves moving from broader period-based results or pushbacks to smaller, more detailed “segments” of areas.

3. Set a new mining sequence for the areas and configure their parameters.

4. Design and apply the haulage network.

5. Configure the dumping points and processing plant destinations.

6. Add excavators, assign their productivity, define repair periods, and set excavation sequences.

7. Adjust the mining parameters based on the planning results.

Next, based on the configured scenario, the excavators begin mining the deposit, and we will be able to track the face positions and the amount of material extracted on each day of the plan. After that, we analyze the obtained results and make adjustments if necessary.

It is also worth noting that short-term planning can likewise use an automated approach with optimal extraction-sequence search. In this case, before assigning the excavators, we can run an automatic calculation to check whether the desired daily targets can be achieved.

Analyzing Results for Continuous Improvement

- So, what should the results of our planning look like?

- What do we need to see clearly and transparently?

- What indicates that the plan is successful?

All of these answers lie in the results-analysis stage. The first and most representative output is the main RoM chart. A detailed evaluation of all results should proceed only after the planner is satisfied with this chart. If not, the analysis must be performed in the opposite direction – to identify what is preventing the plan from reaching the intended targets.

Now, let’s take a look at the chart.

It may look something like this. The key requirement is that it includes all essential indicators: the amount of valuable material, the amount of waste, and the quality. Additional breakdowns by rock types can also be added, which makes the chart even more informative.

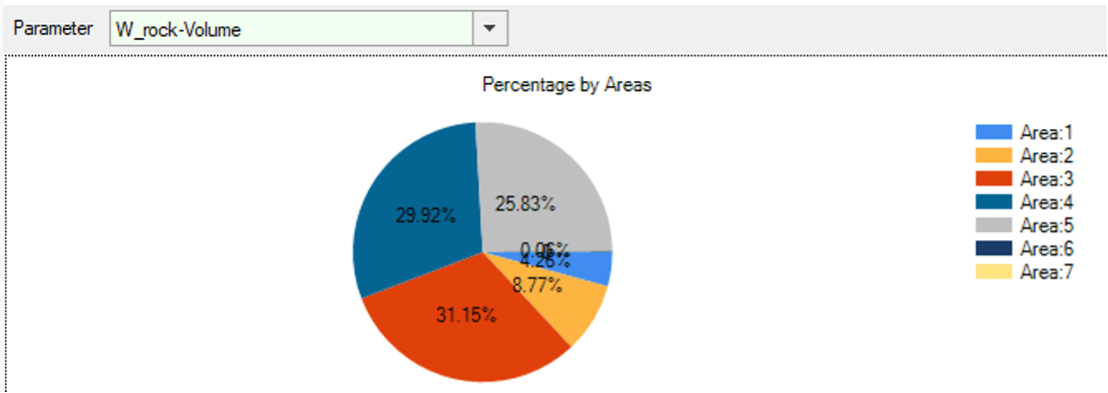

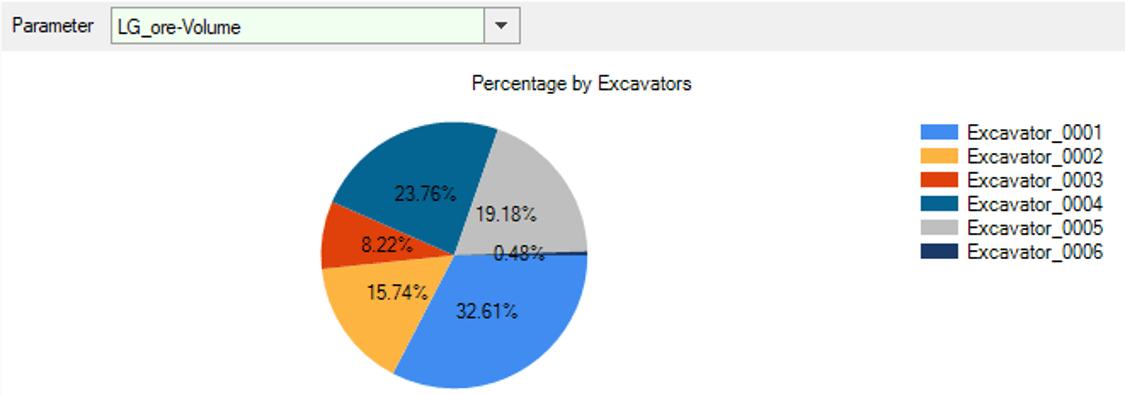

In our standard package, this chart is included by default, as it is one of the primary outputs. We also provide charts that show the distribution of material extraction – either by excavators or by areas. This information helps determine, at a general level, whether the plan has been structured correctly.

These charts are “live,” meaning we can select any indicator we want to visualize, and the data will update instantly. The next type of analytical output is tables – the most detailed and most demanding part, as they contain all the nuances and answers to most questions.

We have several prepared tables, and they show the following:

1. Excavator performance report on the areas. It shows, for each time interval, which excavator extracted what volume of material and with what quality.

2. Area participation report in the haulage process. It shows from which area and bench, during which period, what volume and quality of material was hauled.

3. Haulage network reports. These are extremely important, and most of the analytical focus should be placed here.

3.1 Report categorized by loading points and material types. These two indicators are separated. All others – such as excavation equipment, dumping points, etc. – are grouped, and numerical values are calculated using weighted averages or cumulative methods, depending on the indicator.

3.2 Report categorized by dumping points, with all other indicators aggregated analogously to the previous item.

3.3 Report categorized by material types.

3.4 Report tracking material transported from stockpiles to processing plants.

3.5 General report combining all the data according to the mining intervals.

Reports in section 3 also calculate additional parameters such as material-transport tonne-kilometers (TKM), lift height, and haulage distance. These parameters are among the most important for analysis and decision-making. When needed, any resulting table can be used to generate a chart or exported to Excel for deeper analysis.

Another useful feature is the ability to create virtual columns. These columns can contain any formula for further calculations – even calculations of final product output. For this, you only need the relationship between material quality and product recovery, plus the relevant recovery coefficient and other optional factors.

One of the special capabilities of our planning module is the haulage network. It is configured to satisfy all defined constraints while selecting the shortest haulage route.

This task is universal: it can evaluate any configured scenario, including quality constraints at stockpiles or the plant, maximum stockpile capacity per interval, and more. It can also automatically distribute haulage flows between stockpiles according to optimality criteria.

Let’s summarize what a comprehensive planning approach in K-MINE provides:

1. Full coverage of the entire mine-planning cycle – from long-term strategic planning to weekly and daily short-term plans, including their designs.

2. Smooth transition from one planning stage to another.

3. Detailed, transparent information for result analysis and informed decision-making in complex situations, thanks to the complete planning cycle being handled in one environment.

4. No need for multiple software tools or data-format conversions to maintain workflow continuity.

5. Maximization of profitability by selecting the optimal development scenario – achieved through planning and design modules and the ability to create numerous scenarios.

6. Stabilized ore quality delivered to the processing plant, reducing production costs through improved blending.

7. Increased equipment efficiency by minimizing unnecessary relocations.

8. Additional capabilities enabled by integrating all modules in a single environment built on a unified database.

9. Reduced risks and negative outcomes through early identification of potential issues and timely corrective measures.

10. Maximization of resource recovery through optimal extraction design – and much more.

Back

Back