In mining, it is surprisingly easy to look successful while quietly destroying value. Production is up. Cash cost per tonne is down. Quarterly EBITDA looks great. The board is happy, management gets their bonus, investors see green numbers. And yet, five years later, the same operation struggles with collapsing margins, unstable plans, rising dilution, and a mine life that somehow became shorter instead of longer.

In mining, it is surprisingly easy to look successful while quietly destroying value. Production is up. Cash cost per tonne is down. Quarterly EBITDA looks great. The board is happy, management gets their bonus, investors see green numbers. And yet, five years later, the same operation struggles with collapsing margins, unstable plans, rising dilution, and a mine life that somehow became shorter instead of longer.

This is not bad luck. This is short-term optimization doing exactly what it is designed to do.

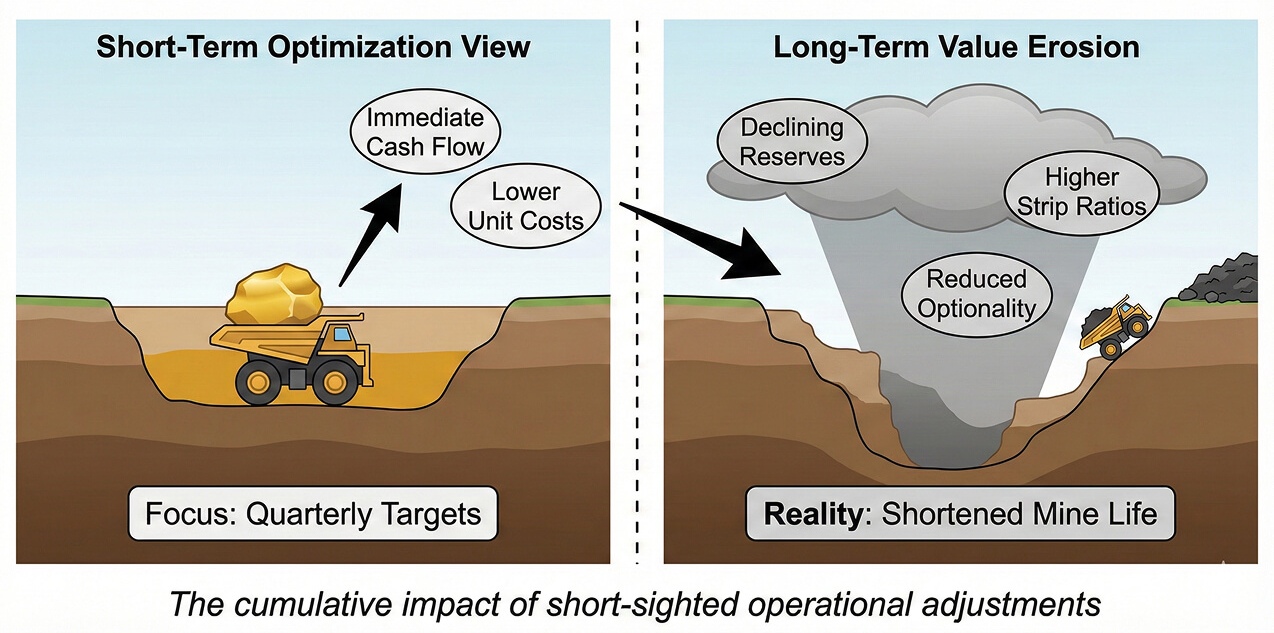

Across the industry, we see the same pattern repeating. Operations chase near-term targets by selectively mining higher-grade zones, postponing waste stripping, compressing development schedules, or simplifying mine plans to hit quarterly KPIs. On paper, the numbers improve fast. In reality, recoverable reserves decline, sequencing flexibility disappears, and future cash flows become weaker and riskier. According to multiple public feasibility reviews and post-mortem analyses, aggressive high-grading alone can reduce life-of-mine NPV by 10–30% even when short-term cash flow improves.

The problem is structural. Most mining organizations are managed on quarterly horizons, while the asset itself behaves on a 10–30 year timescale. A pit wall does not care about EBITDA this quarter. A stope does not adjust itself to a revised budget forecast. Once you break sequencing logic, geotechnical assumptions, or grade distribution, the damage is permanent. You cannot “optimize it back” later.

What makes this especially dangerous is that short-term optimization often looks rational in isolation. Production teams hit tonnage targets. Finance teams see immediate margin improvement. Planning teams are asked to reforecast faster, cheaper, simpler. Each decision, taken alone, makes sense. Taken together, they slowly convert a robust life-of-mine plan into a fragile, reactive operation.

This article is about that gap. Not theory, not software marketing, not hindsight wisdom. It is about how short-term thinking quietly erodes long-term mine value, why this happens even in well-run operations, and what mining teams can do to balance cash flow pressure without sacrificing the future of the asset.

What Short-Term Optimization Really Looks Like in Mining

Short-term optimization in mining is rarely a single, dramatic decision. In practice, it appears as a sequence of operational adjustments that individually look logical, defensible, and even financially responsible, but collectively erode the long-term value of the asset.

One of the most common examples is grade front-loading. During periods of price volatility or capital pressure, operations often prioritize higher-grade zones to stabilize cash flow. This approach typically improves head grade by 5–15% in the short term and reduces unit costs on a per-tonne basis. However, multiple post-audit studies of open pit gold and copper operations have shown that sustained grade front-loading can reduce life-of-mine NPV by 10–30%, primarily due to shortened mine life and the loss of flexibility in later years.

A well-documented case comes from a mid-tier open pit gold operation in West Africa. Between Years 2 and 4 of operation, management approved aggressive grade prioritization to meet debt covenants. Annual gold production exceeded plan by nearly 12%, and all short-term financial metrics improved. By Year 6, however, the operation faced a steep decline in recovered grade, while remaining material required higher strip ratios and longer haul distances. A subsequent re-optimization of the LOM plan showed a 22% reduction in NPV compared to the original feasibility case, despite higher cumulative ounces produced in the early years.

Deferred waste stripping is another classic short-term lever, particularly in large open pits. By delaying waste removal, operations can temporarily improve strip ratios and reduce reported mining costs. The economic impact is often underestimated. In several publicly disclosed post-feasibility reviews of large copper operations in South America, aggressive stripping deferral led to a 15–25% increase in sustaining capital requirements during the second half of mine life, combined with higher operational risk due to steeper pit walls and reduced scheduling flexibility.

In underground mining, short-term optimization frequently takes the form of reduced development. Capital and operating budgets are trimmed by cutting lateral development, limiting the number of active stoping areas, or compressing development schedules. While this may improve short-term cost metrics, it significantly reduces optionality. A Canadian underground base metal mine provides a clear example. After two consecutive years of reduced development to protect cash flow, the operation entered a period where unplanned ground conditions in a single mining block reduced annual production by over 18%. The lack of alternative stopes and prepared development left the operation with no viable short-term recovery options.

There are also less visible forms of short-term optimization that occur at the planning and modeling level. Simplifying geological domains, reducing block model resolution, or limiting scenario analysis are often justified by time pressure. However, internal benchmarking across multiple operations has shown that overly simplified models tend to underestimate dilution and overestimate recovery, leading to systematic bias in production forecasts. These discrepancies often only become apparent several years into operation, at which point corrective action is expensive and limited.

What unites these examples is not poor engineering or lack of expertise. In most cases, the technical teams were fully aware of the trade-offs. The real driver is organizational structure and incentive design. When performance is measured primarily on annual production, unit cost, or short-term cash flow, decisions that damage long-term value become not only acceptable but rational.

Short-term optimization in mining is therefore not a tactical problem. It is a systemic one. It emerges naturally when long-life assets are managed with short reporting horizons, and when decision-making authority is fragmented across departments with competing objectives.

High-Grading: The Fastest Way to Destroy Life-of-Mine Value

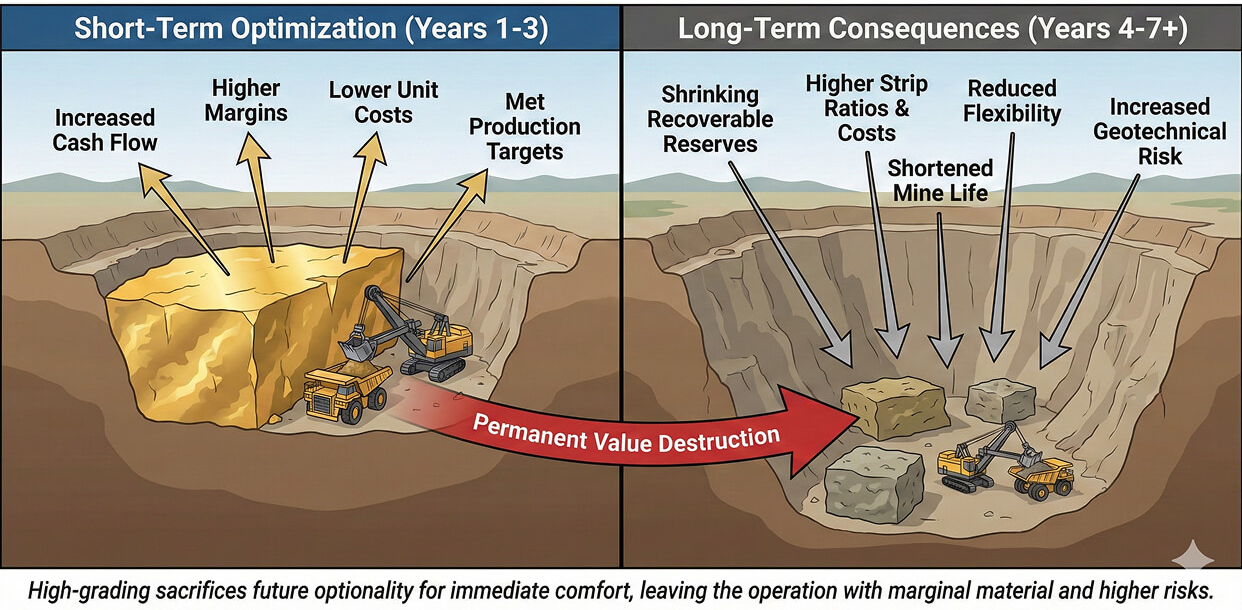

High-grading is one of the most widely used and least honestly discussed forms of short-term optimization in mining. Almost every operation does it at some point. Almost every feasibility study warns about it. And yet, it remains one of the fastest ways to permanently destroy life-of-mine value while appearing financially successful in the short term.

At its core, high-grading means prioritizing higher-grade material earlier in the mining sequence, usually to improve cash flow, meet production targets, or compensate for price pressure. In isolation, the logic is simple and hard to argue against. Higher grades mean higher metal output per tonne, better recoveries, lower unit costs, and stronger margins. The problem is that ore bodies are not bank accounts. You cannot withdraw the best material today without changing the economics of what remains tomorrow.

The immediate financial effect of high-grading is usually positive and measurable. Head grades increase by 5–20%, payable metal rises, and cash costs per unit drop. In several publicly reported gold operations, short-term grade uplift resulted in a 10–15% improvement in operating margins within the first two years. This is exactly why high-grading is so attractive under pressure.

The long-term impact, however, is far more severe and often underestimated. By pulling high-grade material forward, operations compress the grade distribution of the remaining reserve. Lower-grade material that was originally blended with higher-grade zones becomes marginal or uneconomic. As a result, cut-off grades creep upward, recoverable reserves shrink, and mine life shortens. Multiple retrospective analyses across gold, copper, and polymetallic operations show reserve losses in the range of 5–25% following sustained periods of aggressive high-grading.

A well-known example comes from an open pit gold mine in Australia. During the first four years of operation, management consistently approved grade front-loading to maintain strong cash flow during a period of weak gold prices. Annual production exceeded the feasibility forecast by an average of 8%, and early-year EBITDA was significantly above plan. However, when the operation reached Year 7, the remaining reserve base had a materially lower average grade than originally modeled. A re-estimation of reserves reduced total mineable ounces by approximately 18%, and the revised LOM plan showed a 27% reduction in NPV compared to the original feasibility study, despite higher cumulative production in the early years.

High-grading also breaks sequencing logic. Most mine plans are designed around a balance between grade, geotechnical stability, haulage efficiency, and processing constraints. When higher-grade zones are selectively extracted out of sequence, this balance collapses. In open pits, this often leads to steeper interim slopes, longer haul distances earlier than planned, and higher exposure to geotechnical risk. In underground mines, selective stoping of high-grade areas can leave behind irregular voids, compromised ground conditions, and inefficient access to remaining blocks.

An underground zinc-lead operation in Europe provides a clear illustration. Over a three-year period, high-grade stopes were prioritized to meet smelter commitments and short-term revenue targets. Development into lower-grade areas was postponed. While concentrate output initially increased, the operation later faced severe sequencing constraints, with isolated stopes requiring additional development and ground support. The result was a sustained increase in operating cost of more than 20% in later years, alongside a reduction in recoverable reserves due to inaccessible blocks.

Another often overlooked consequence of high-grading is its impact on processing performance. Plants are typically designed and optimized for a certain feed grade range and mineralogical profile. Sustained deviations from this profile can reduce recovery, increase reagent consumption, or accelerate wear on equipment. Several copper operations that implemented aggressive grade front-loading reported higher-than-expected variability in metallurgical recovery, partially offsetting the assumed benefits of higher head grade.

Perhaps the most dangerous aspect of high-grading is that it is rarely reversed. Once high-grade material is extracted, it cannot be put back. When market conditions improve, the operation is left with fewer options to capture upside. Instead of extending mine life or increasing production, management is forced to focus on cost containment and risk management, often under worse geological and operational conditions than originally planned.

It is important to stress that high-grading is not inherently wrong. In certain scenarios, such as genuine liquidity crises or short-term price collapses, limited and carefully modeled grade prioritization can be justified. The problem arises when high-grading becomes a default operating mode rather than a controlled exception. In many operations, it quietly shifts from a temporary measure into a structural feature of the mine plan, without a full reassessment of its long-term economic impact.

In mining, value is not created by extracting the best material as fast as possible. It is created by extracting the right material in the right sequence, under the right economic assumptions, across the full life of the asset. High-grading does the opposite. It sacrifices future optionality for immediate comfort, and the bill always arrives later, usually when the operation can least afford it.

Short-Term KPIs vs Life-of-Mine Economics

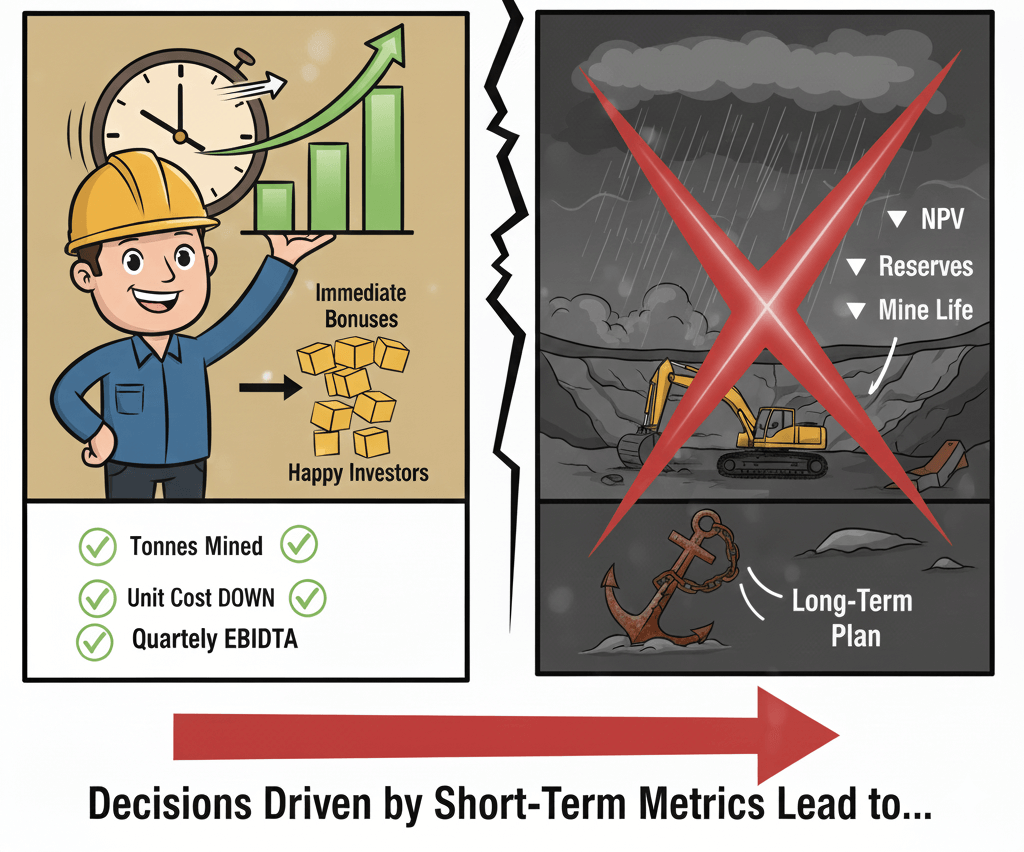

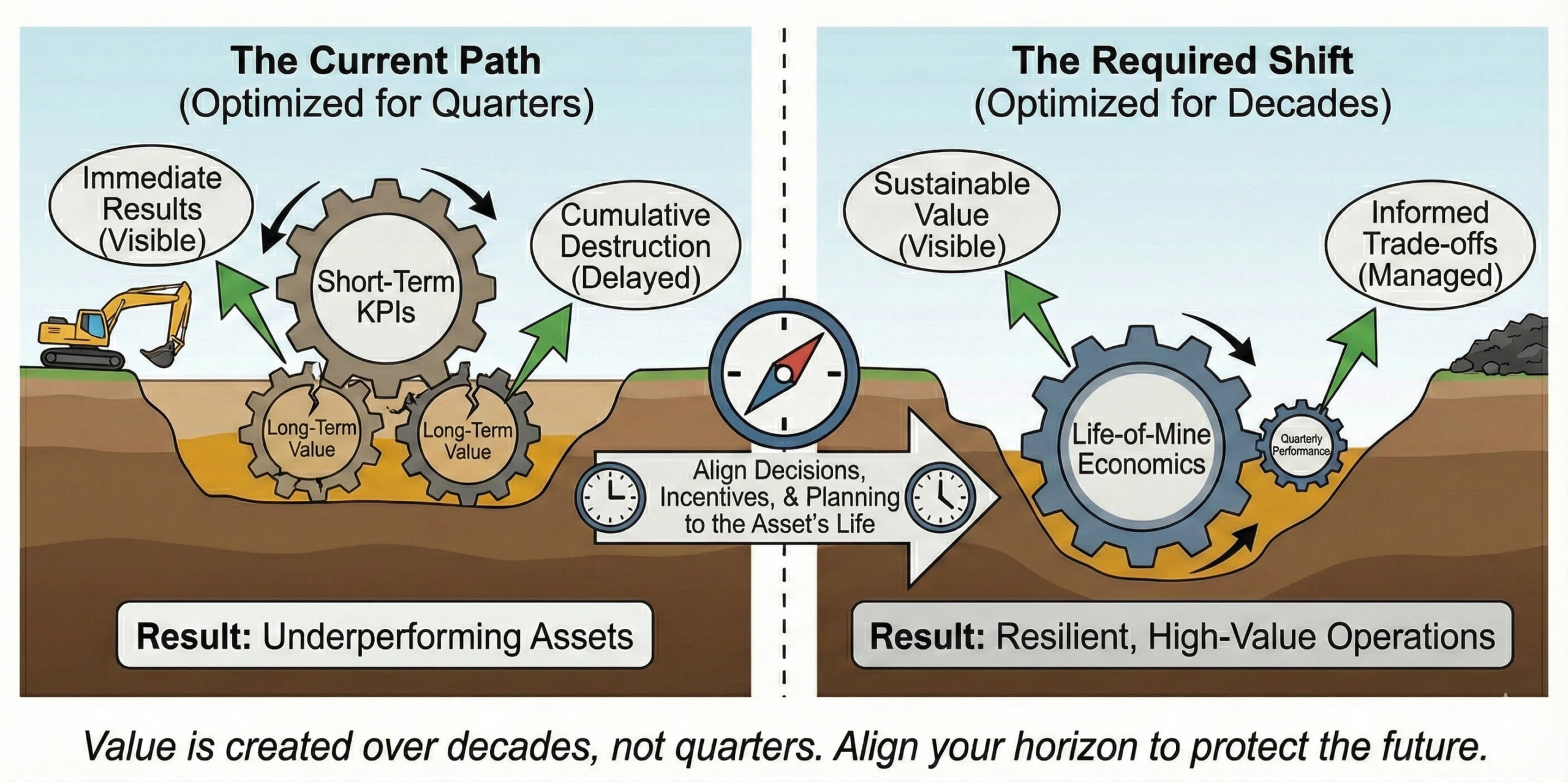

One of the main reasons short-term optimization persists in mining is not a lack of technical understanding. It is the way performance is measured, reported, and rewarded. In most operations, decision-making is driven by short-term KPIs that are poorly aligned with life-of-mine economics.

Typical operational KPIs are well known: tonnes mined, metal produced, cash cost per tonne, cost per pound, budget variance, and quarterly EBITDA. These metrics are easy to track, easy to explain to investors, and useful for monitoring day-to-day performance. The problem starts when they become the primary basis for strategic decisions in a long-life asset.

Life-of-mine value, on the other hand, is driven by very different variables: sequencing quality, reserve integrity, flexibility of the plan, long-term capital efficiency, and risk-adjusted cash flow over decades. These factors rarely move in the same direction as quarterly KPIs.

A common example is production maximization. Many operations are incentivized to meet or exceed annual tonnage and metal targets. When geological conditions deteriorate or operational constraints appear, the fastest way to stay on target is often to mine higher-grade areas faster or simplify the mining sequence. The KPI is met. The plan is technically “delivered”. But the economic cost of that decision is not visible in the current reporting cycle.

This disconnect is not theoretical. In several large open pit operations reviewed after major re-planning exercises, it was found that annual production targets were met consistently, while the underlying life-of-mine schedule drifted further away from the original feasibility case each year. By the time a full LOM re-optimization was performed, cumulative deviations had reduced projected NPV by more than 20%, even though no single year showed a dramatic operational failure.

Cost-focused KPIs create similar distortions. Cost per tonne and cost per unit of metal are among the most closely watched metrics in mining. Under pressure, teams naturally prioritize actions that reduce these numbers in the short term. Deferred stripping, reduced development, simplified ground support, or narrower mining widths can all improve reported costs. However, these decisions often increase long-term costs through higher dilution, lower recovery, re-handling of material, or the need for corrective work later in the mine life.

An underground gold operation in North America provides a clear illustration. For several years, the mine consistently outperformed its unit cost targets by reducing development and focusing on easily accessible stopes. Short-term margins improved, and cost KPIs were celebrated. When the operation later attempted to restore its original production profile, it faced a development backlog that required a significant increase in capital spending. The revised life-of-mine plan showed a lower overall IRR than the original feasibility, despite years of “cost discipline”.

Another structural issue is that life-of-mine metrics often sit outside individual accountability. NPV, reserve depletion rate, or long-term schedule robustness are typically reviewed at a corporate or strategic level, not owned by a single department. Production managers are measured on output. Planning teams are measured on forecast accuracy. Finance teams are measured on budget control. No one is directly rewarded for preserving optionality ten years down the line.

This fragmentation leads to rational local optimization and irrational global outcomes. Each team does exactly what it is asked to do. The mine as a system suffers.

The timing mismatch makes the problem worse. The negative effects of short-term decisions usually materialize years later, often under different management or market conditions. By then, the original drivers of the decisions are no longer visible, and the consequences are treated as external factors: geology disappointment, market volatility, or unforeseen technical challenges.

Importantly, this is not an argument against KPIs themselves. Short-term metrics are necessary to run a complex operation safely and efficiently. The issue is using them as proxies for value creation. When short-term KPIs dominate decision-making without a clear link to life-of-mine outcomes, the operation is effectively optimized for reporting cycles rather than for asset value.

Operations that manage to escape this trap tend to do one thing differently. They explicitly connect short-term decisions to long-term economic impact. Changes to sequencing, cut-off grades, or development rates are evaluated not only against next quarter’s forecast, but against their effect on mine life, reserve quality, and long-term cash flow under multiple price scenarios. This does not eliminate trade-offs, but it makes them visible and deliberate.

In mining, what gets measured gets optimized. If the horizon of measurement is too short, the optimization will be too short as well. Life-of-mine value does not disappear because people ignore it. It disappears because the system rewards decisions that slowly undermine it.

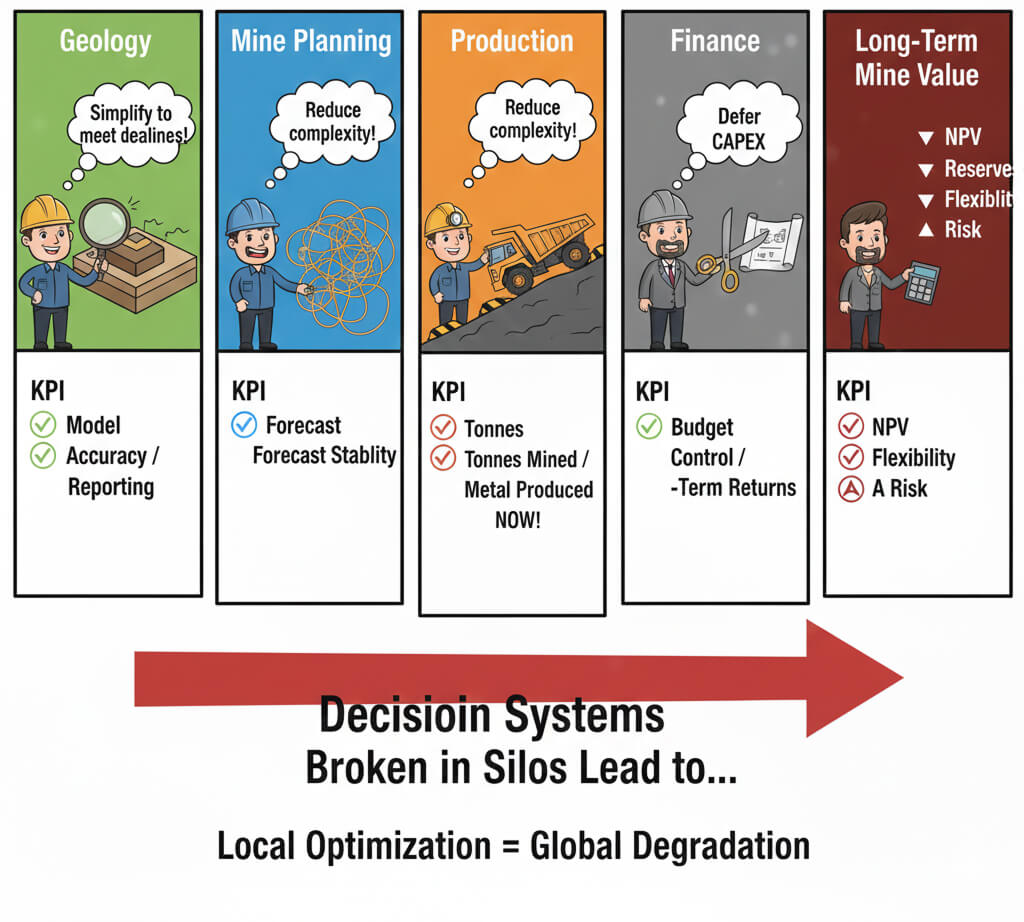

Planning Fragmentation: When Departments Optimize Against Each Other

In many mining operations, long-term value is not destroyed by bad decisions. It is destroyed by too many good decisions made in isolation.

Mining is a system, but it is rarely managed as one. Geology, mine planning, production, processing, and finance all operate with different objectives, different time horizons, and different definitions of success. Each function optimizes its own slice of the operation, often with limited visibility of how those optimizations interact.

Geology typically focuses on resource confidence, grade continuity, and reserve conversion. Their success is measured by model accuracy, reconciliation, and compliance with reporting standards. When under pressure, geological models are often simplified to accelerate planning cycles or to meet reporting deadlines. Domains are merged, uncertainty is averaged out, and risk is hidden rather than eliminated. From a geological perspective, this may be acceptable. From a mine planning perspective, it introduces systematic bias that only becomes visible years later.

Mine planning teams, in turn, are usually measured on forecast accuracy and schedule stability. When plans start to drift, the fastest way to restore alignment is often to reduce complexity. Fewer scenarios, fewer constraints, fewer contingencies. The plan becomes easier to execute on paper, but less resilient in reality. Long-term flexibility is sacrificed to protect short-term plan adherence.

Production teams live in an even shorter time horizon. Their primary objective is to deliver tonnes and metal safely, today and tomorrow. When plans do not match reality, production adapts. Higher-grade areas are pulled forward. Marginal zones are bypassed. Temporary solutions become permanent operating practices. From the production perspective, this is not poor discipline. It is survival in a system that does not tolerate missed targets.

Finance adds another layer of fragmentation. Budgets are typically annual, sometimes quarterly. Capital allocation decisions are made based on short-term returns and cost control. Development, waste stripping, and infrastructure investments that primarily benefit later years are easy targets for deferral. The financial logic is clear. The operational consequences are delayed and often invisible in the same reporting cycle.

A large open pit copper operation provides a good illustration. Geological models were updated annually, mine plans quarterly, and budgets yearly. Each cycle optimized locally. Over time, inconsistencies accumulated. The mine plan increasingly relied on material that had lower confidence, longer haul distances, and higher strip ratios than originally assumed. Production continued to meet annual targets, but with rising operational effort. When a full integrated re-planning exercise was finally performed, it became clear that the remaining mine life had significantly less optionality than expected, and projected sustaining capital increased materially.

Underground operations experience similar issues, often with even less visibility. Reduced development approved by finance may look like a reasonable cost-saving measure. For planning, it reduces future flexibility. For production, it increases exposure to any local disruption. When something goes wrong, the root cause is rarely traced back to a decision made several budget cycles earlier. Instead, the problem is framed as operational underperformance or geological risk.

The most dangerous aspect of planning fragmentation is that no single decision appears catastrophic. The damage emerges from interaction effects. A slightly simplified geological model feeds into a slightly compressed mine plan, which feeds into a production adjustment to hit targets, which is then reinforced by a budget reforecast. Each step makes sense on its own. Together, they systematically degrade long-term value.

This fragmentation is often reinforced by organizational structure. Departments have clear boundaries, clear responsibilities, and clear KPIs. What they rarely have is shared ownership of life-of-mine outcomes. Long-term metrics such as reserve quality, schedule robustness, or downside risk rarely belong to anyone operationally. They exist in reports, not in incentives.

Operations that manage to avoid this trap tend to break one rule. They treat mine planning as an integrated economic process, not as a sequence of departmental handovers. Geological uncertainty, operational constraints, and financial trade-offs are evaluated together, using a common horizon and common economic objectives. This does not eliminate conflict between departments, but it makes trade-offs explicit instead of accidental.

When departments optimize against each other, the mine does not fail immediately. It slowly becomes brittle. And brittle systems in mining eventually break, usually at the worst possible moment.

Why Software Alone Does Not Fix Short-Term Thinking

When mining operations start feeling the consequences of short-term optimization, one of the most common reactions is to look for a technical solution. Better planning tools. Faster scheduling engines. More dashboards. More integration. The expectation is simple: if decisions are wrong, better software will fix them.

In reality, software rarely changes the horizon of decision-making. It only accelerates whatever behavior already exists.

Modern mine planning and optimization tools are powerful. They can generate schedules faster, process larger datasets, and evaluate more scenarios than ever before. But they do not decide what the objective function should be. If the organization is optimizing for quarterly production, unit cost, or short-term cash flow, software will simply help achieve those targets more efficiently, even if doing so destroys long-term value.

This pattern is visible across many operations that invested heavily in advanced planning platforms without changing governance or incentives. In several large-scale open pit operations, the introduction of sophisticated optimization tools led to more frequent re-planning cycles. Plans were updated monthly instead of quarterly. Scenarios were generated faster. Yet the economic outcomes did not improve. In some cases, they worsened. Frequent re-optimization under short-term pressure led to constant resequencing, further erosion of long-term logic, and increased operational volatility.

A common failure mode is using long-term tools with short-term objectives. Life-of-mine optimizers are often repurposed to solve near-term production problems. Instead of protecting long-term value, they are used to squeeze additional tonnes or grade out of the next few periods. The mathematical solution may be optimal for the defined objective, but the objective itself is misaligned. The result is technically correct optimization of the wrong problem.

Another issue is false confidence. Sophisticated software produces precise outputs: detailed schedules, clean numbers, smooth curves. This precision can mask structural weaknesses in the underlying assumptions. Simplified geological domains, optimistic recovery factors, or constrained development rates are carried through the model with great numerical accuracy. The plan looks robust because it is well-structured, not because it reflects reality.

There are also organizational side effects. When planning tools become more complex, fewer people fully understand how decisions are made. Optimization parameters, constraints, and economic assumptions are often adjusted by specialists under time pressure. The broader team sees the output, not the trade-offs embedded in it. This reduces transparency and makes it harder to challenge short-term driven decisions, especially when they are wrapped in technically sophisticated models.

Importantly, software does not resolve fragmentation. A planning platform cannot align geology, production, and finance if these functions continue to operate on different horizons. Integration at the data level does not automatically create integration at the decision level. Many operations have fully connected systems where geological models, mine plans, and financial forecasts technically talk to each other, yet decisions are still made sequentially and defensively.

This does not mean software is irrelevant. On the contrary, the right tools are essential for managing long-life, high-complexity assets. But their impact depends entirely on how they are used. Operations that successfully balance short-term pressure with long-term value treat software as a decision support system, not as a decision-making authority. Long-term objectives are defined first. Short-term actions are evaluated explicitly against their impact on mine life, reserves, and risk. Software is used to make trade-offs visible, not to hide them behind optimization outputs.

The uncomfortable truth is that short-term thinking is not a technology problem. It is a governance and incentive problem. As long as performance is measured and rewarded primarily on short-term metrics, no amount of software sophistication will protect life-of-mine value. In fact, better tools may simply allow organizations to make the same mistakes faster and with greater confidence.

Mining projects are not destroyed by a lack of data or computational power. They are destroyed when tools designed for long-term optimization are forced to serve short-term objectives. Software can amplify good decision-making, but it cannot replace it. And it certainly cannot change the time horizon of an organization that is not ready to change it itself.

What Long-Term Optimization Actually Looks Like

Long-term optimization in mining does not mean ignoring short-term reality. Cash flow matters. Production targets matter. Markets are volatile and capital is finite. The difference is not in whether trade-offs exist, but in how consciously and systematically they are managed.

Operations that preserve life-of-mine value tend to share a few practical characteristics. None of them are theoretical. All of them come from hard-earned experience.

The first is scenario-driven planning instead of single “optimal” plans. Rather than treating the life-of-mine schedule as a fixed blueprint, leading teams work with multiple economically ranked scenarios. Different price assumptions, development rates, cut-off strategies, and sequencing options are evaluated side by side. The objective is not to find one perfect plan, but to understand how sensitive value is to key decisions. In practice, this often reveals that small short-term gains come at a disproportionate long-term cost.

A large copper operation in North America adopted this approach after several years of reactive re-planning. Instead of updating a single LOM every quarter, the planning team maintained a small set of economically distinct scenarios. When short-term pressure emerged, management could see not only the impact on next year’s cash flow, but also the effect on mine life and downside risk. Over time, this reduced ad-hoc resequencing and stabilized long-term value, even though short-term metrics became slightly less aggressive.

The second characteristic is rolling life-of-mine optimization. In many operations, the LOM plan is treated as a static document updated infrequently. In contrast, high-performing teams continuously reconcile actual performance against long-term assumptions and adjust the plan in a controlled way. Geological updates, recovery trends, and operational constraints are fed back into the economic model regularly, not to chase short-term targets, but to preserve consistency between reality and long-term intent.

An underground gold mine in Scandinavia provides a strong example. The operation implemented a rolling LOM review cycle where any proposed short-term deviation had to be evaluated against its impact on reserve quality and mine life. This did not prevent short-term adjustments, but it forced them to be explicit and reversible where possible. As a result, the mine maintained stable production while extending its reserve base over time, despite operating in a relatively narrow margin environment.

Another key element is economic-driven sequencing rather than grade-driven sequencing. Instead of prioritizing blocks purely based on grade, long-term optimization focuses on net value contribution, considering mining cost, processing behavior, recovery, and timing of cash flows. This often leads to counterintuitive decisions, such as mining moderate-grade material earlier to preserve access, flexibility, or blending options later.

Several open pit operations that shifted from grade-first to value-first sequencing reported lower head grades in the early years but higher cumulative cash flow and longer mine lives. In these cases, early discipline created optionality that allowed the operations to capture upside when market conditions improved, rather than being trapped with marginal material and limited choices.

Long-term optimized operations also tend to integrate risk explicitly. Instead of optimizing on a single expected outcome, they consider downside scenarios. Geotechnical uncertainty, development delays, and recovery variability are incorporated into planning decisions. This does not eliminate risk, but it changes behavior. Plans become more conservative in the right places and more flexible where it matters.

Equally important is governance. In operations that successfully balance short-term pressure and long-term value, life-of-mine metrics are not abstract concepts owned by corporate strategy. They are operationally visible. Decisions that materially affect mine life, reserve quality, or long-term capital requirements require cross-functional review. This slows some decisions down, but it prevents irreversible value destruction.

Crucially, these operations accept that long-term optimization sometimes means accepting less attractive short-term numbers. Production may be flatter. Unit costs may be slightly higher in early years. But these outcomes are understood as investments in flexibility and resilience. Over the full life of the asset, they consistently outperform operations that chase early wins and pay for them later.

Long-term optimization in mining is not about being conservative. It is about being deliberate. It replaces reactive decision-making with structured trade-offs and replaces short-term comfort with long-term control. It does not eliminate pressure. It simply ensures that pressure does not silently rewrite the future of the mine.

How Leading Mining Teams Balance Cash Flow and Long-Term Value

Mining teams that consistently preserve long-term value are not immune to short-term pressure. They face the same price volatility, capital constraints, and stakeholder expectations as everyone else. The difference lies in how they structure decisions when trade-offs are unavoidable.

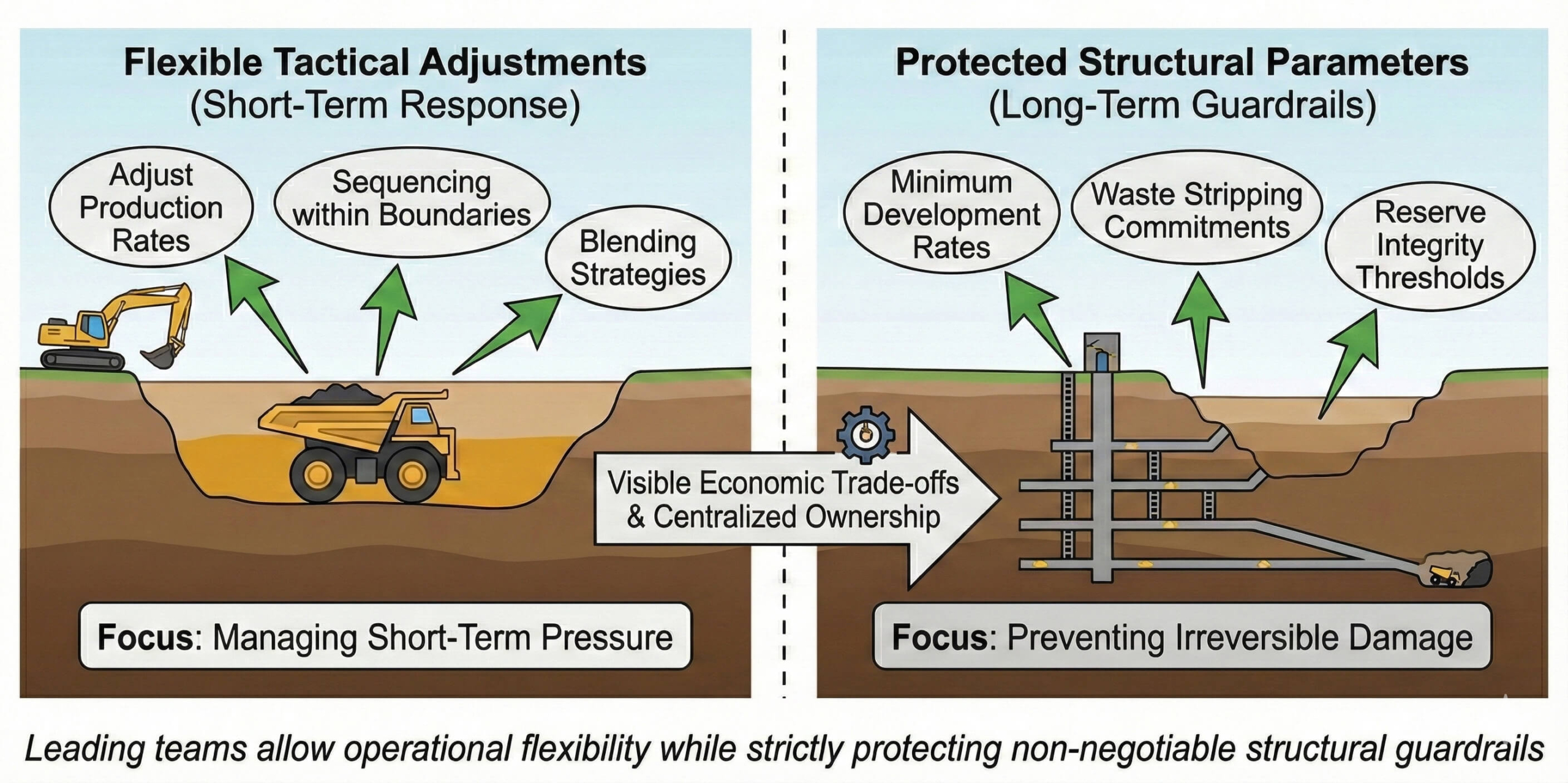

One common pattern is explicit separation between tactical adjustments and structural changes. Leading teams allow flexibility at the operational level, adjusting production rates, sequencing within defined boundaries, or blending strategies to respond to short-term conditions. At the same time, they protect a small number of non-negotiable structural parameters: minimum development rates, waste stripping commitments, access to critical areas, and reserve integrity thresholds. These constraints act as guardrails. They do not prevent optimization, but they prevent irreversible damage.

A large underground copper operation in South America adopted this approach after experiencing repeated production volatility. Management introduced minimum development and access requirements that could not be reduced without executive approval, regardless of short-term cost pressure. While this occasionally resulted in higher reported costs in weak price environments, it gave the operation the ability to recover quickly when conditions improved. Over a full cycle, the mine delivered higher cumulative cash flow and lower operational risk than comparable assets that aggressively cut development.

Another common trait is making economic trade-offs visible at decision time. Instead of approving short-term actions based solely on next-quarter impact, leading teams require a clear statement of long-term consequences. This does not need to be a full feasibility rework. In many cases, a simplified economic delta is enough: impact on mine life, reserve ounces or tonnes, sustaining capital, and downside exposure. The key is not precision, but transparency.

An open pit gold operation in Latin America implemented a formal “value impact” check for all major resequencing decisions. Over time, this revealed a consistent pattern: many actions that improved near-term cash flow by a few percent carried long-term value penalties several times larger. Once these effects were made visible, behavior changed. Fewer ad-hoc changes were approved, and short-term pressure was addressed through operational efficiency rather than structural compromise.

Successful teams also tend to centralize ownership of life-of-mine outcomes. Rather than treating LOM value as a corporate abstraction, they assign clear accountability. This may take the form of a cross-functional planning committee or a dedicated role responsible for long-term value preservation. The exact structure varies, but the intent is the same: someone is explicitly responsible for protecting the future of the asset, not just delivering the next plan.

Importantly, these teams are disciplined about when short-term sacrifice is justified. Liquidity crises, covenant pressure, or temporary market dislocations may require pulling value forward. The difference is that these decisions are treated as exceptions, not defaults. They are time-bound, documented, and revisited. When conditions stabilize, the operation actively works to rebuild flexibility, rather than continuing in survival mode out of habit.

There is also a noticeable difference in how these teams communicate with stakeholders. Rather than promising smooth, ever-improving short-term metrics, they explain the logic behind their trade-offs. Investors and boards are shown not only what the plan delivers next year, but what it protects over the next decade. While this requires confidence and discipline, it often leads to more stable expectations and fewer reactive interventions.

What emerges from these examples is not a single best practice, but a consistent mindset. Cash flow is treated as a constraint, not as the objective function. Short-term performance is managed, not worshipped. Long-term value is actively defended, even when doing so is uncomfortable.

In mining, the teams that outperform over the full cycle are rarely the ones with the most aggressive early numbers. They are the ones that understand when to push and when to hold, and that recognize the difference between flexibility and fragility.

Stop Optimizing the Wrong Horizon

Mining projects rarely fail because of a single bad decision. They fail because of hundreds of small decisions that were perfectly rational in the short term and quietly destructive in the long term.

Short-term optimization is not a mistake. It is a natural response to pressure. Price volatility, capital constraints, operational uncertainty, and stakeholder expectations all push teams toward immediate results. The real problem begins when short-term thinking becomes the dominant lens through which a long-life asset is managed.

Throughout this article, the pattern is consistent. High-grading improves early cash flow but compresses future value. KPI-driven decisions deliver clean quarterly results while degrading reserve quality and flexibility. Fragmented planning allows departments to optimize locally while the system as a whole loses coherence. Even advanced software, when used without the right governance, accelerates the same behavior instead of correcting it.

What makes this especially dangerous is timing. The benefits of short-term optimization are immediate and visible. The costs are delayed, cumulative, and often attributed to external factors when they finally appear. By the time mine life shortens, sustaining capital spikes, or operational risk increases, the original decisions are long forgotten.

Operations that consistently create value over the full cycle do not avoid trade-offs. They manage them differently. They make long-term consequences visible at the moment decisions are made. They protect a small number of structural elements that preserve optionality. They treat life-of-mine value as an operational responsibility, not a theoretical concept buried in corporate reports.

Most importantly, they optimize across the right horizon. They accept that a mine is not a quarterly instrument. It is a long-term economic system with irreversible constraints. Once sequencing is broken, access is lost, or reserves are degraded, no amount of short-term performance can fully restore what was given up.

The uncomfortable truth is that many mines are not underperforming because of geology, markets, or technology. They are underperforming because they are optimized for reporting cycles rather than for asset value. Changing this does not require perfect foresight or heroic discipline. It requires acknowledging that value is created over decades, not quarters, and aligning decisions, incentives, and planning processes accordingly.

In mining, the question is rarely whether short-term optimization will improve results today. It almost always will. The real question is whether those improvements are worth the value they quietly destroy tomorrow.

Back

Back