Kriging Neighborhood Analysis (KNA) in geology is a geostatistical method used to optimize the parameters of kriging, a geostatistical estimation technique, to improve the accuracy and reliability of mineral resource estimations. Specifically, KNA helps minimize conditional bias, a common issue in kriging where estimated block grades are less variable than actual block grades.

Kriging Neighborhood Analysis (KNA) in geology is a geostatistical method used to optimize the parameters of kriging, a geostatistical estimation technique, to improve the accuracy and reliability of mineral resource estimations. Specifically, KNA helps minimize conditional bias, a common issue in kriging where estimated block grades are less variable than actual block grades.

Most resource estimation methods use some form of grade smoothing to interpolate values into a block based on surrounding samples. The process of determining a suitable sample search scheme is often called kriging neighborhood analysis, and a user’s guide to implementing this is discussed in Vann, Jackson, and Bertoli (2003). These methods can be divided into two categories: non-geostatistical and geostatistical.

Non-geostatistical grade interpolation methods use some relationship between the distance of a sample from the block center and a weight assigned to it. The most commonly used approach weights each sample by some power of the inverse of its distance from the block being estimated (IDW).

All geostatistical approaches to grade interpolation are based on some form of kriging, where the weight applied to each choice is based on a semi-variogram model that defines continuity. These geostatistical methods can be divided into three classes: linear kriging, nonlinear kriging, and simulation modeling.

Linear kriging methods are the easiest to apply and are based on simple or ordinary kriging and its variations. When resource modelling by kriging, a number of estimation parameters must be established, such as block model size, minimum and maximum number of samples, etc.

If the interpolation of contents in a block of a block model was carried out using the ordinary or simple kriging method, then to categorize resources it is necessary to calculate several attributes showing the quality of the assessment results for each block (including the presence of a biased estimate).

In most modern software products, these parameters are calculated automatically. Different Software packages incorporate KNA functionality to assist geologists in this process. With the release of K-MINE 2025, Kriging Neighborhood Analysis (KNA) is now available when performing geostatistical analysis.

In this article, we will look at the main KNA metrics and their impact on resource estimation.

The main KNA metrics

To assess kriging performance, a set of metrics collectively referred to as Kriging Neighbourhood Analysis (KNA) is employed, such as kriging variance, kriging efficiency, slope of regression, magnitude of negative weights, etc. By optimizing these parameters, KNA aims to minimize conditional bias, which is the difference between the estimated block grades and the actual average grade of the mined blocks.

Block Size Optimization

To assess kriging performance, a set of metrics collectively referred to as Kriging Neighbourhood Analysis (KNA) is employed, such as kriging variance, kriging efficiency, slope of regression, magnitude of negative weights, etc. By optimizing these parameters, KNA aims to minimize conditional bias, which is the difference between the estimated block grades and the actual average grade of the mined blocks.

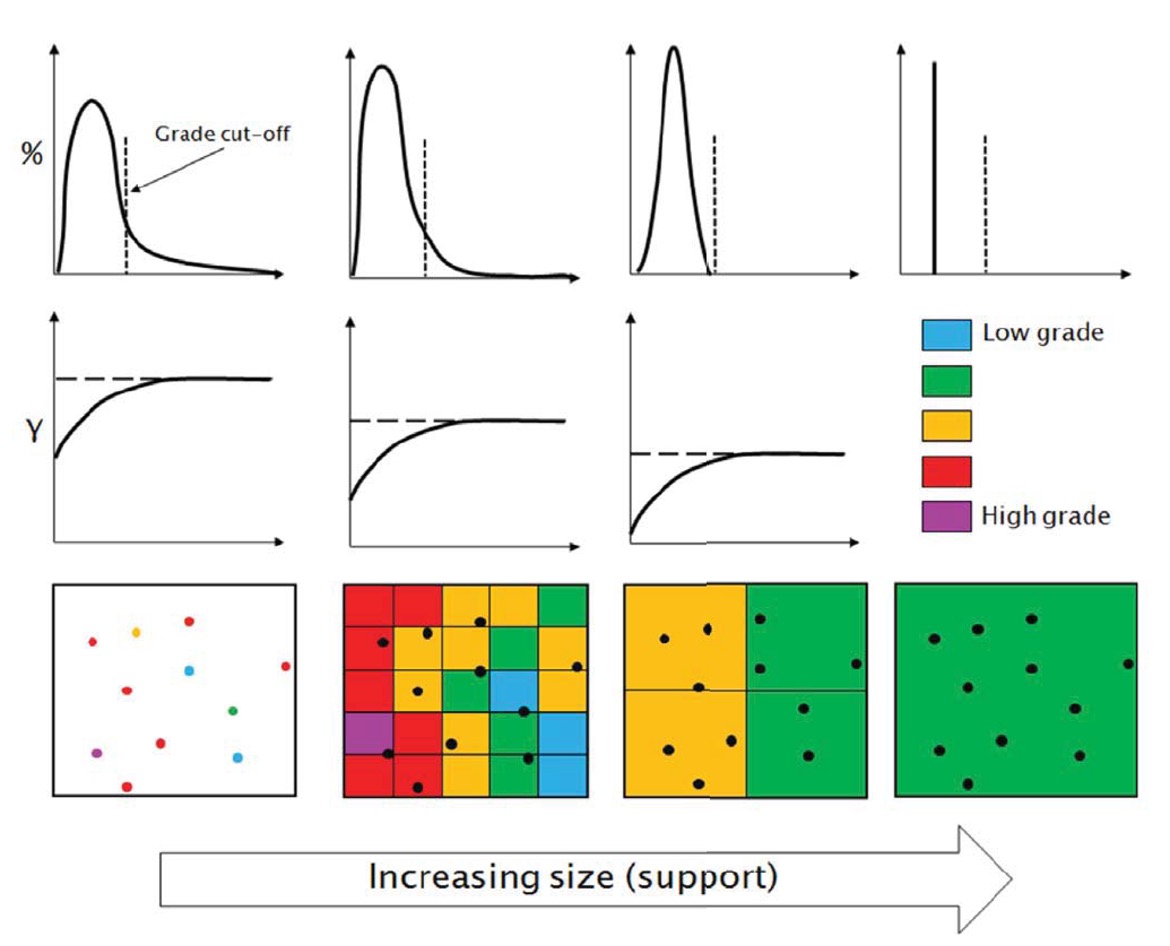

FIG. 1 – Illustration of the volume-variance effect or the change in support from points through to the whole-of-domain on the distribution of grade and the variogram

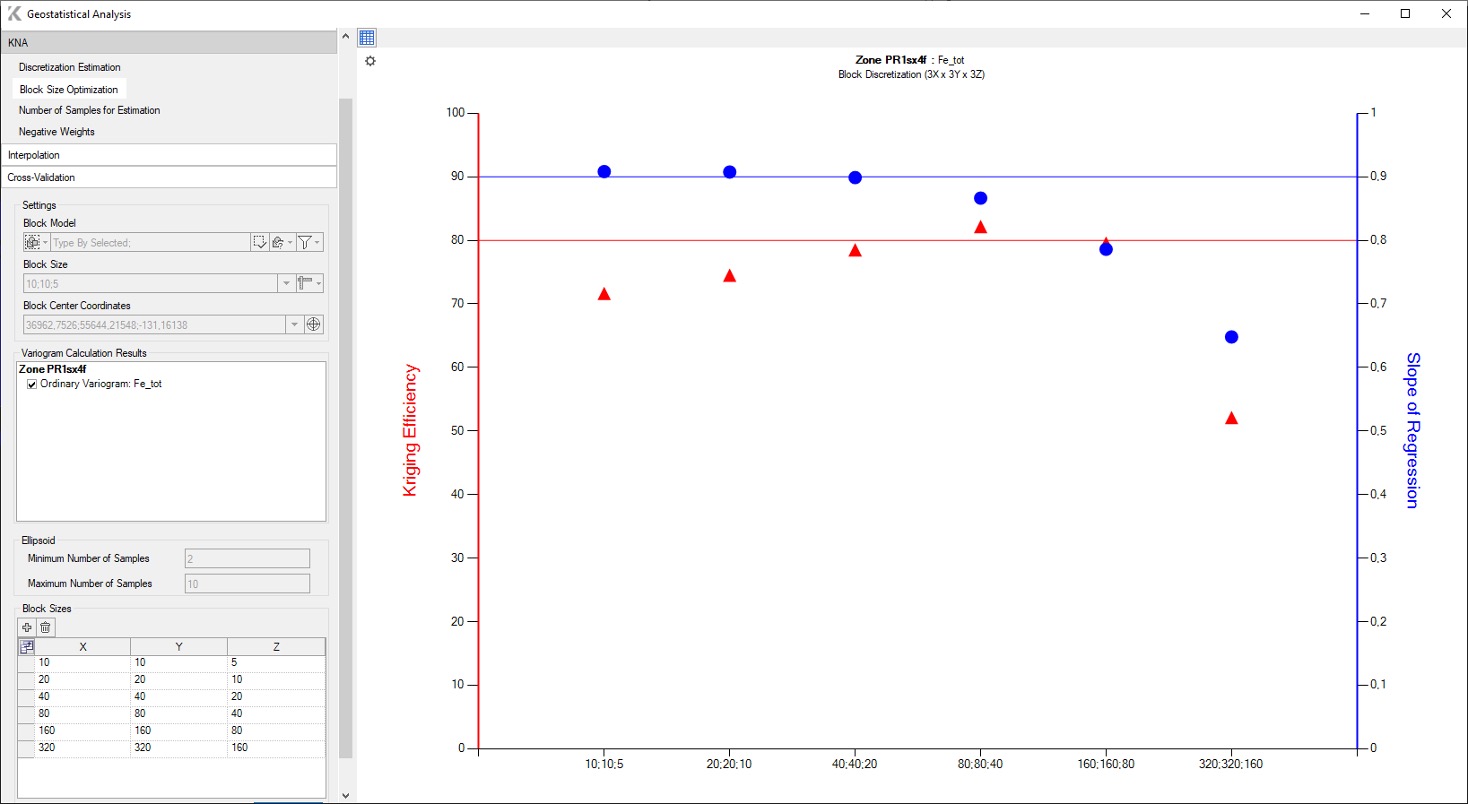

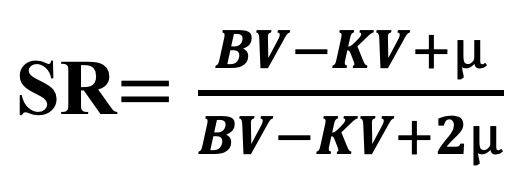

Determining the block size requires careful evaluation of many factors, including engineering considerations, ore deposit geometry, equipment size, and data spacing. Figure 2 shows that, based on the efficiency of kriging and regression slope, the optimal block size is 80*80*40.

FIG. 2 – Block size optimization in K-MINE

However, it should be remembered that the concept of “optimal” must be defined for each situation. The discussion should shift from conditional bias to the purpose of the assessment and the objectives of the study.

Kriging Efficiency

Kriging Efficiency (KE) was introduced by Krige (1996) as a metric for evaluating the efficiency of block estimates. The equation for KE is:

![]()

where KV is the kriging variance, and BV is the block variance.

The equation for BV is:

![]()

where μ is the Lagrange multiplier, λi are the kriging coefficients, γ(xi,xo) is the variogram value for distances in pairs: sample-estimation location (block center).

A high KE signifies a low KV, indicating the presence of numerous closely spaced data points and minimal smoothing in the estimate. Conversely, a low KE implies a high KV, suggesting a scarcity of local data and the potential for a smoothed estimate.

Kriging variance

The kriging variance is the minimized error of the kriging estimation, i.e., the expected squared difference between the true value and the estimated value. Kriging variance is calculated using the covariance values (obtained from the variogram) and the weights assigned to the data points in the search space (Barboza I. and Deutsch C., 2024). The equation for KV is:

![]()

where μ is the Lagrange multiplier, λi are the kriging coefficients, γ (xi,V) is the arithmetic mean value of γ along the variogram for the distances to all sampling points in the block from the point xi, γ (V, V) is the arithmetic mean value of γ along the variogram between all sampling points within the block.

KV, in conjunction with Kriging Efficiency, serves as a closely interrelated set of parameters for assessing the performance of Kriging.

The calculation of KV is closely related to discretization, since it requires the calculation of the average gamma over the discretization points in a block, and not just over the center point in the block, as in the calculation of BV.

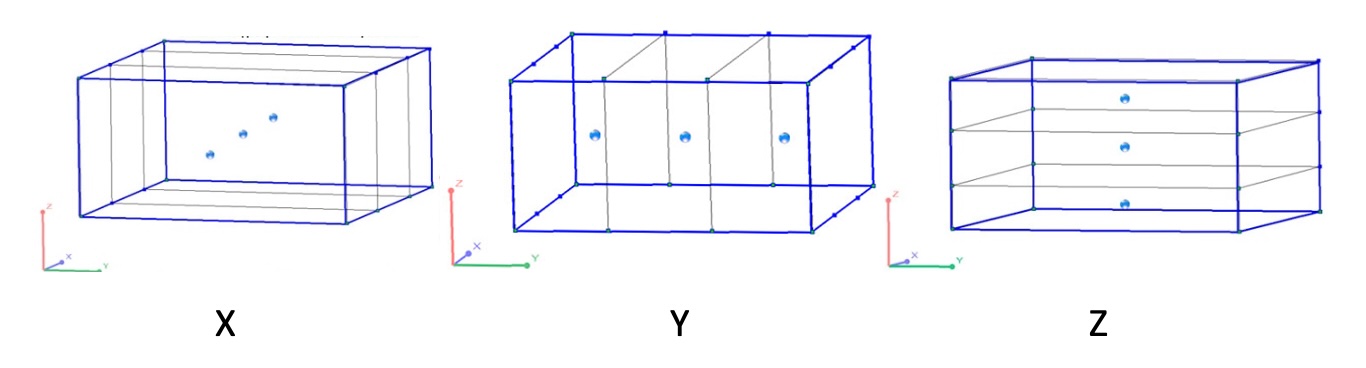

The principle of discretization is to estimate the average value within a specified local area (in K-MINE, within a virtual block, the coordinates of the center of which and the dimensions are specified in the starting settings).

To do this, the user must specify the number of discrete points inside the block. Discretization points are the centers of cells within the estimated block (FIG.3). Each point is estimated (as a point estimate), and the average value of these points is the block estimate. The number of discretization points corresponds to the number of cells into which the block is divided.

FIG. 3 – The number of discretization points in axes directions in K-MINE

The initial size of the block and the coordinates of its center are specified by the user. Then, depending on the number of specified discrete points, the original block is equally divided into the corresponding number of cells in the X, Y, and Z directions, and the coordinates of the centers of the formed subblocks will correspond to the discretization points. That is, the number of discrete points determines the number of subblocks.

For example, if for a starting block with the edge size along the X, Y, and Z axes of 10×10×5, the combination of discrete points is specified: in the X direction=3, in the Y direction=3, in the Z direction=3. This means that the block is evenly divided into three cells along three axes. The edge size of the sub-blocks is: for X=10/3=3.33m, for Y =10/3=3.33m, for Z =5/3=1.66m, and the number of discrete points (sub-block centers) in the starting block will be: 3×3×3=27.

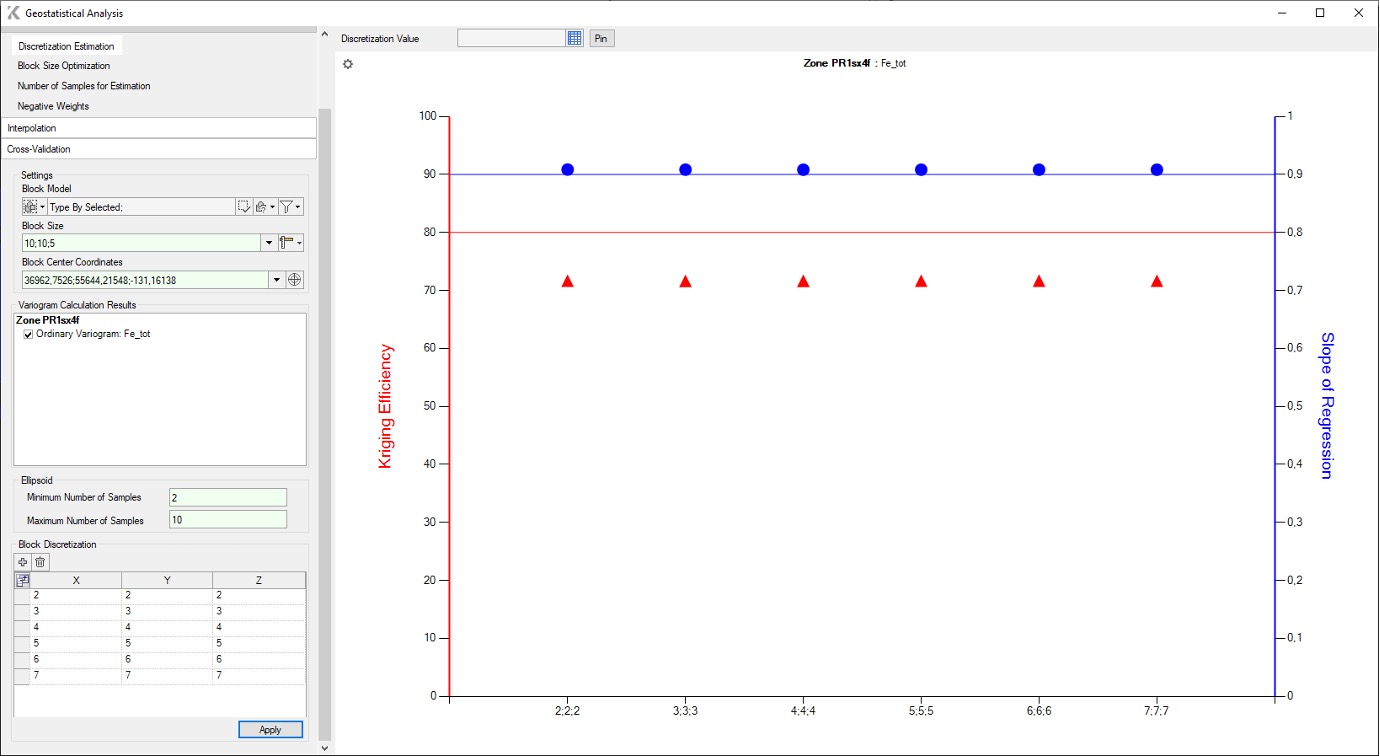

The graph in Fig. 4 shows a horizontal line in red, corresponding to a Kriging Efficiency value of 80%. This line serves as a guide for the user when choosing the optimal number of sampling points.

FIG. 4 – Discretization estimation in K-MINE

The optimal discretization option is determined by the points on the graph located as close as possible to the red (kriging efficiency 80%) and blue lines (slope of regression 0.9).

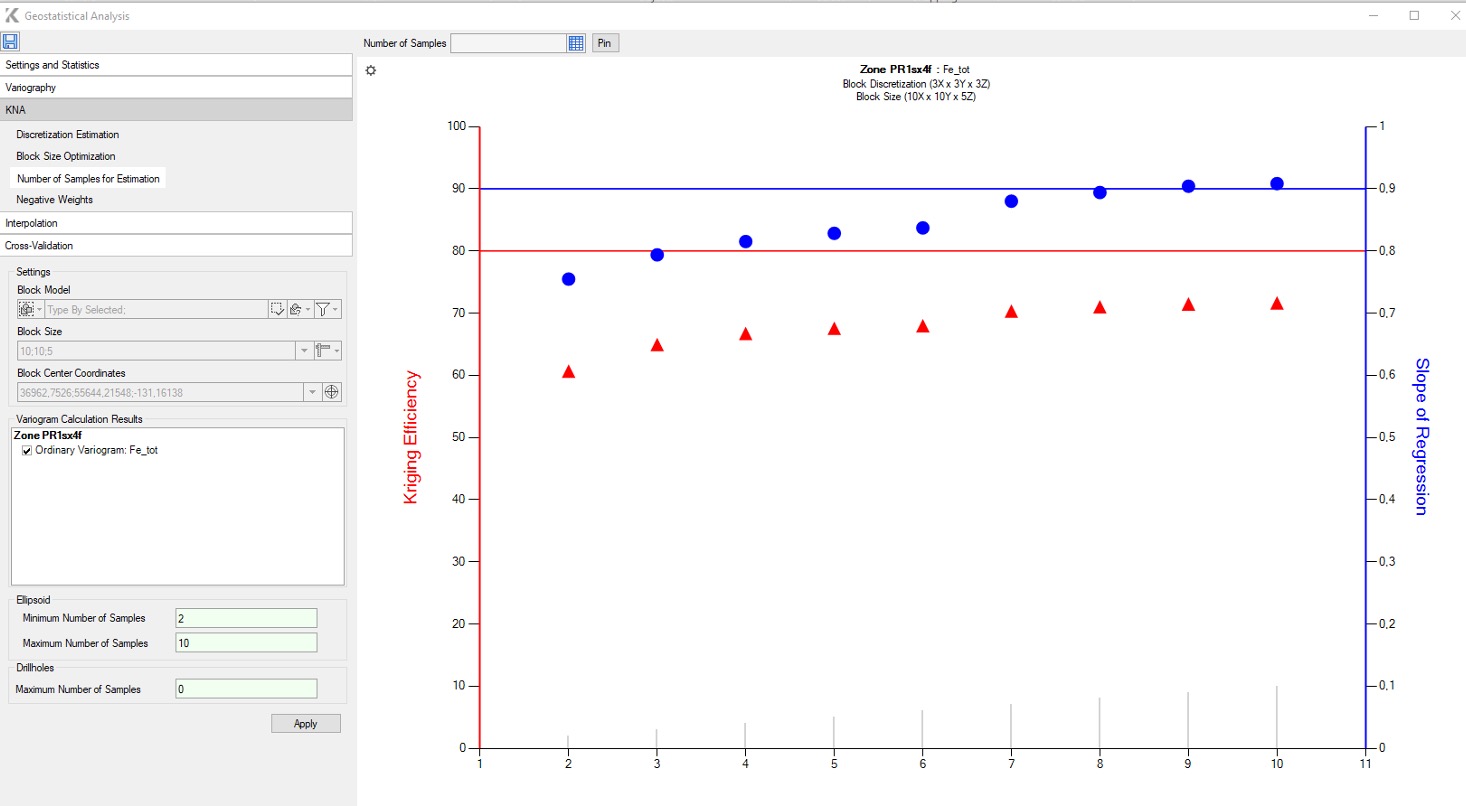

Slope of Regression

The Slope of Regression (SR) provides a measure of conditional bias, measuring the slope of the linear regression of the true value on the estimate. This is directly observed in cross-validation, but can also be theoretically calculated on a block-by-block basis using expected values derived from covariances.

where µ is the Lagrange multiplier when calculating KV.

The slope of the regression line, which accounts for the true and estimated values, is often used to diagnose conditional bias. Ideally, the slope of this line should be equal to one, which implies conditional unbiasedness.

Both the slope of regression and the kriging efficiency should be treated with caution. Imputed bias reduction may not be an appropriate approach to estimating metal grades, especially in deposits that require high cutoff grades for extraction.

Conditional bias is a serious problem if the estimate is to be used to make a final or near-final decision, such as for grade control in an open-pit mine or for estimating stopes in underground. If the estimate is intended to separate waste and ore at the end of production, then smoothing is justified to prevent conditional bias.

However, if your grade estimates are intended for an intermediate planning stage and more detailed information becomes available in the future to separate ore and waste at production conditions, then smoothing will be a problem because it will not reflect the correct grade-tonnage relationship that can be expected during production (Glacken I. and Trueman A., 2014).

Number of Samples for Estimation and Negative Weights

The calculation of these indicators is performed to confirm the optimal choice of the unbiased kriging estimate with the optimal block size.

When clicking on a marker, the corresponding values are visualized on the graph, and the user must select and pin the most acceptable maximum and minimum sample values (FIG. 5).

FIG. 5 – Number of samples estimation in K-MINE

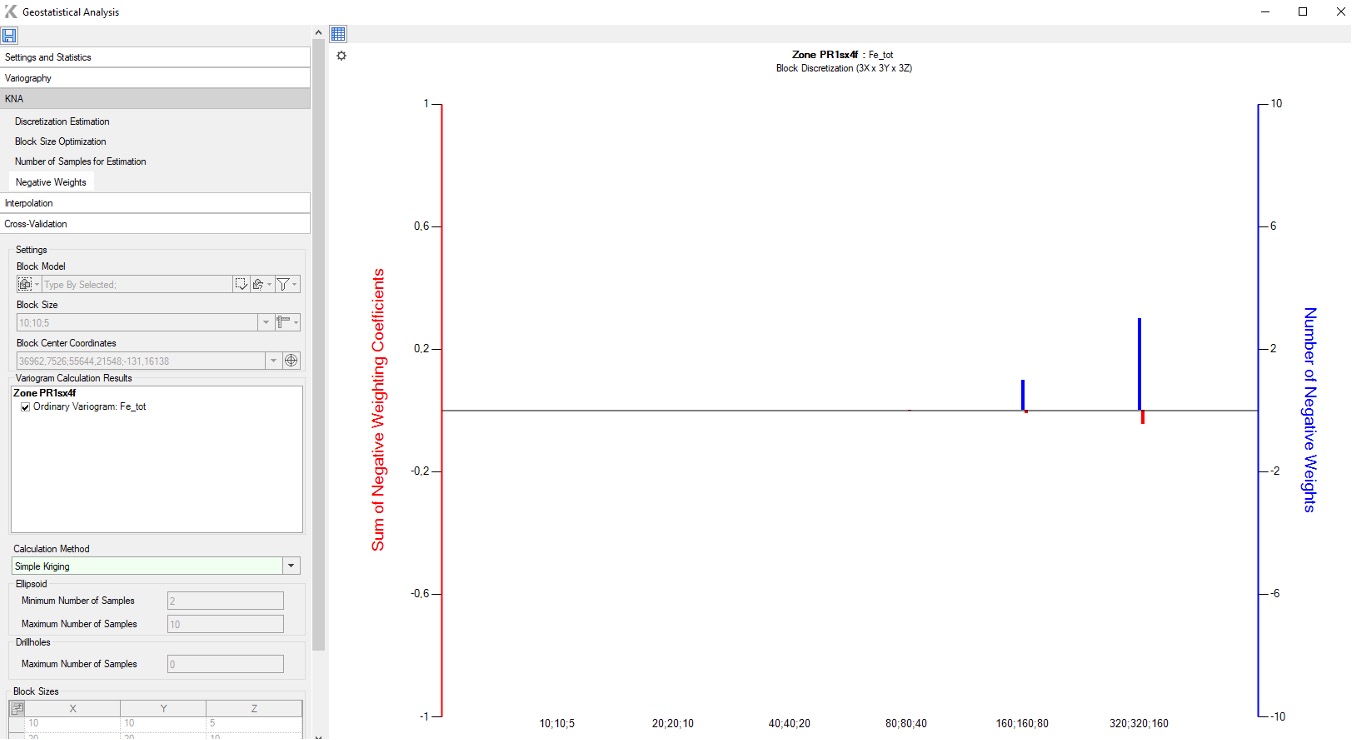

In the framework of interpolation, negative kriging weights may appear at the search boundary. Their presence indicates the selection of reliable interpolation parameters, but their number in the total mass of samples participating in the interpolation should not exceed 5%. If the number of weights exceeds the specified value, there is a risk of obtaining an unreliable result.

In zones of lower sample density or where there is no sampling, at least one negative weight is present. Blank space in the map represents blocks where there are only positive weights. In Simple Kriging, the Slope of Regression is always one.

The calculation of the number of negative kriging weights and the sum of negative weights in K-MINE is performed for all block sizes specified in the “Block size optimization” tab with previously selected and fixed settings: the number of sampling points, the minimum and maximum number of samples, and the minimum number of samples from one drillhole (FIG. 6).

FIG. 6 – Negative weights estimation in K-MINE

After accepting the appropriate parameters, users can proceed to the next stages of interpolation and validation of the block model. K-MINE supports Simple and Ordinary Kriging, Kriging with external drift, Cokriging, etc.

Discussion

KNA can be integrated into resource estimation workflows, allowing geologists to optimize parameters directly within the software and apply these optimized settings to the final grade estimation. Geologists are constantly challenged to provide precise resource estimates faster, better, or cheaper.

On the one hand, software helps to implement multiple iterations faster, but at the same time, the need for understanding geostatistical methods and interaction with many other disciplines is growing. The relationship between cut-off grade, variogram, sampling step, required degree of smoothing, and estimated recovery selectivity is a complex problem.

Including factors of geometallurgy, geotechnics, etc. in the model estimation, a geologist must have knowledge in these areas. Powerful computing technology is a good tool only in the hands of a professional.

There is a debate within the resource estimation community about two opposing goals: minimizing global conditional bias and ensuring local block accuracy. In dense sample density environments, both goals are achievable, but in the pre-development and feasibility stages of a mine cycle, it is rarely possible to simultaneously minimize global bias and ensure local grade accuracy. Krige (1996) discusses tools for measuring (and thus minimizing) conditional bias in an estimate, while Isaaks (2004) discusses the paradox of attempting to achieve an unbiased but locally accurate estimate. In the Glacken and Trueman (2014) opinions, most estimators succeed in achieving either a conditionally unbiased or a locally accurate estimate, and for most, the focus is on achieving minimum conditional bias at the expense of local accuracy.

The final task of resource estimation is to assign classification categories for resource confidence. It is quite common to hear debates among geologists about the block model parameters that need to be taken into account when assigning resource categories to Measured, Indicated, and Inferred.

In polygonal methods, resources are usually classified using the total drilling density. Another approach is to take into account the average distance from the block center of the samples used to estimate the block, or simply the number of samples identified in the search volume. This involves multiple estimation runs and increasing the search radius of the samples. In this case, blocks are estimated using the most distant samples with the lowest confidence category. The disadvantage of this automated approach is the infamous “spotted dog” effect and the violation of the necessary requirement for orebody continuity.

Approaches to classifying resource categories based on the kriging variance or the error introduced during estimation are also popular. The kriging variance is a good indicator of the total distance between samples, accounting for anisotropy and clustering of samples. Other numerical approaches include the regression coefficient and the kriging efficiency indices proposed by Krige.

To summarize all of the above, resource classification is based on a combination of numerical and geological criteria with the necessary supervision of a competent person.

The development of conditional modeling and the use of powerful computing technology and artificial intelligence open up new prospects for the creation of universal complex modules that combine resource modeling with optimization and planning of mining operations. This is the direction in which K-MINE is moving.

Back

Back